jdowning - 7-31-2008 at 06:40 AM

In chapter 6 of "Structure of the Arabian and Persian Lute",

Dr H. G. Farmer translates part of the 15th C. Kitab kashf al-humum (preserved in the Top Qapu Saray Library at Stamboul) including comments about the

best woods from which to make an oud.

According to Salih ibn 'Abdallah ibn Karim al-Nisaburi, the ancients used four kinds of wood (for the bowl?) these being Beech (zan), Elm (dardar),

Walnut (saz = shiz= sasam) and Vine (mais) - which have qualities not found in other woods. He goes on to give some of these qualities. Beech gives a

ringing tone; elm gives a fineness (of tone?); walnut lasts forever and resists insect attack. For Vine he makes the mysterious comment that it has a

quality 'only to be found in the treasury of kings'.

I have never used Vine as a wood or know of it being used for instrument making in modern times. If the Vine referred to is Grape Vine (or a species

of Grape Vine), it is a wood that is common to this part of the world. Indeed, as a woodlot owner (a tree farmer - of sorts), I regard the wild vine

as a pest plant in that it grows quickly and can eventually overcome and kill any tree that it climbs. For this reason part of maintaining the wood

lot is to cut any vine found climbing a healthy tree - a never ending task. The tree farm was planted about 25 years ago on redundant farm land but

there are also many trees of venerable age growing in the original field fence-lines of the farm - including some large, well developed vines. Rather

than clear out and waste these old vines, I thought that it might be interesting to use them in an experimental investigation to determine if this

wood might be suitable for oud making.

I shall start with a vine patch that has stems over 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter. This vine plant appears to be dead so the wood may be partially

seasoned (if it is not rotted). There are also many vines of lesser size - cut in recent years and now dry - to experiment with.

Vine seems an unlikely wood to me but there is only one way to find out. "Nothing ventured, nothing gained".

This is not a good time of year to work in the woods due to the high humidity and proliferation of biting insects so will likely get into the project

later this year.

In the meantime, does any one know of Vine being used in modern times for oud bowl construction - or any kind of woodwork for that matter?

GeorgeK - 7-31-2008 at 07:41 AM

Very nice topic, I look forward to reading how this progresses.

I'm curious on how you plan on experimenting with the wood? Are

your interests from a structural point of view or are you planning

on doing some tone quality experiments? If its the latter then,

if you dont mind, can you post on how you plan to proceed, ie

experiment setup, how you plan on rating the quality of the tone, do you plan on comparing varoius species of wood, etc...

Again, a very nice topic and I look forward to your progress.

SamirCanada - 7-31-2008 at 07:48 AM

I thought Sesam refered to Indian Rosewood.

Marina - 7-31-2008 at 08:09 AM

Samir, I also got the oud with Sesam bowl - newer know what does it mean.

Walnut or Indian RosewoodEnybody? It has reddish color.

paulO - 7-31-2008 at 10:40 AM

Looks more like a type of rosewood to me. The walnut I've seen has less pronounced contrast in the grain and tends to be more of a uniform brown. This

is one beautiful oud, whether walnut or rosewood !

Regards,

Paul

DaveH - 7-31-2008 at 11:59 AM

Interesting concept. I have this image in my head that vinewood would have a very low density and splits all over the place, but maybe that's because

of the way the bark looks and feels. I realise I've never actually seen the heartwood.

We are talking of the days of Omar Khayyam here, so I'm guessing if vinewood was used then it was from vineyards and was torn up because the vines

were past their best for fruiting. I'm wondering, if it was very old and had been constantly pruned, it might have ended up denser, harder and

gnarlier, a bit like olivewood or walnut. So, if this doesn't work out so well with wild vinewood, it doesn't necessarily discount your theory.

Another thing I was wondering along these lines - could this reference have been allegorical, or even a sly joke, referring to the fact that vine was

so highly prized by the secular authorities (but not really approved of by the religious ones). Maybe even something along the lines of music sounding

better when you're wasted  . Or perhaps the courtiers preferred to be inebriated

when their kings picked up the oud, what with them having so many other responsibilities and so little time to practice - I've been there.

. Or perhaps the courtiers preferred to be inebriated

when their kings picked up the oud, what with them having so many other responsibilities and so little time to practice - I've been there.

jdowning - 7-31-2008 at 03:36 PM

Not sure about rosewood - I am just quoting Farmer who translates saz=shiz=sasam as walnut. Is 'sesam' the same as 'sasam'? B.t.w. Indian rosewood was

never used for European lutes as it was considered to be an inferior 'tonewood' - perhaps it was the same for early ouds? Indian rosewood has quite an

open grain whereas European walnut is close grained - more suitable for thin ribs I would say (American walnut, is a bit more open grained). Walnut

colour can range between brown and purple and can be very highly figured.

At this early stage, I am just researching available information so have yet to decide on what tests to carry out should the project seem viable. I

might very well end up making an oud with grape vine wood ribs to test my findings. Not sure about comparative 'tone quality' experiments though - too

subjective and life is too short!

Grapes were cultivated in early Arabic cultures to be used for distilling alcohol, not for consumption as a beverage, but for medicinal purposes - it

is said!

So far, I have found few literary references to (grape) vine wood as a woodworking material. These days it is often used for open fire cooking (BBQ)

as it is aromatic when burnt and provides a flavour to cooked meats.

One ancient reference to vine wood is in Ezekiel chapter 15 of the Old Testament of the Holy Bible. I am not qualified to interpret this parable but a

literal summary is that wild vine wood is no good as a woodworking material. It is only good for burning! So, perhaps I am 'barking up the wrong tree'

here and should not waste any more time on this project?

A more recent reference to vine wood is found in the mid

19th C publication "Turning and Mechanical Manipulation, Volume 1" by Charles Holzapffel. The first part of the book deals with materials for turning.

Under 'Apricot - Tree', the author refers to the 18th C French turner, Bergeron, who comments that often those woods that bear agreeable fruits are

not handsome in appearance or agreeable in scent as might be expected. In this category, in addition to Apricot wood, he lists Orange, Lemon, Quince,

Pomegranate, Coffee and Vine "and many others occasionally met with, rather as objects of curiosity, than as materials applicable to the arts"

Both sources indicate that vine was not considered to be a generally useful or commercially available woodworking material - for whatever reasons.

Nevertheless, could vine, in rare circumstances - carefully selected for a specific application - still be a perfectly viable material for making oud

bowls? Lets try and find out.

This afternoon I gathered two small samples of wild grape vine from my wood lot. These had been cut over a year ago so were relatively dry and

seasoned. The samples were each sliced in two on a band saw and the sawn surfaces planed smooth to reveal the grain. The large sample measures 50 mm

in diameter and the small sample 25 mm. No checking or splitting due to drying of the samples is evident. The heart wood is light brown with white sap

wood - medium open grain but less than American Walnut. Inspection of the end grain shows that it is a wood of 'ring-porous' classification - that is

it is a hardwood with relatively small (but visible under low magnification) pores in the early wood and very small (indistinguishable under low

magnification) pores in the late wood. (Other ring porous wood species include Elm, Oak, Ash, Hickory, Chestnut and many others).

Counting the rings in the large sample indicate its age to be about 25 years - so wild vine is not such a fast growing wood after all.

I would judge the density to be 'medium' or perhaps 'medium/heavy' - just guessing, around 0.5 to 0.6 Specific Gravity.

SamirCanada - 7-31-2008 at 08:35 PM

it would probably make for one light oud!

anyways would there be enough wood to make an oud with it??

could it be easily bent? I would think so.. Perhaps with less spring back?

also what part would be used the heatwood or sapwood?

thanks for this John.

its really interesting!!

as for sessam, the word is used now days to define indian rosewood by the oud makers of Iraq more particularly.

jdowning - 8-1-2008 at 06:44 AM

Thanks Samir.

Ouds of today would appear to be much more heavier built than early ouds - using denser hardwoods and thicker sections (and presumably much higher

string tensions and different tone colour) than would have been found in earlier times. Farmer in 'Structure of the Arabian and Persian Lute in the

Middle Ages' quotes from several early texts including:

"It is necessary that the wood of the bowl should be as thin as possible and of even thickness throughout ....". (9th C)

"The wood of the bowl should be thin and made from light wood.." (10th C)

"Seasoned Larch wood should be cut very thin for the soundboard. The bowl should be of thinner wood than the soundboard. The bowls of the best ouds

are made from 11 ribs but sometimes 13 are used" (14th C)

"The wise agree that wood of medium weight is required for an oud - the best wood being 'shah' from Darya-bar or sometimes from Sardia.." (14C)

"An essential to the oud is wood as thin as possible ...... It is agreed that the lighter the wood the better ..." (15C)

From this it would seem that an oud during this time period was constructed more like a European lute with rib thickness of the bowl less than the

thickness of the soundboard. (Rib thickness in surviving lutes can be around 1 mm to 1.5 mm thick).

Indian Rosewood has a specific gravity of around 0.76 compared to Black Walnut (0.55), Elm (0.5 to 0.66), American Beech (0.64), Hard Maple (0.46 to

0.63), Ash (0.56 to 0.61). For comparison Spruce has an s.g of 0.4, Larch 0.52 and Ebony 0.90. So, if my guess is correct and the Vine wood sample has

a specific gravity in the range 0.5 to 0.6 then this would not be out of place as a wood used in the construction of early ouds whereas Indian

Rosewood, Ebony and other dense tropical hardwoods would be considered too heavy.

The heartwood of the vine would be generally used - although the strong colour contrast between heartwood and sapwood might be a useful possibility

(like 'shaded' yew ribs in lutes). The sapwood of vine may not be very durable, however.

The question " would there be enough to make an oud with" is probably the most important consideration. I would not question that the early oud makers

knew what they were talking about when they list vine wood among the superior woods for oud making but obtaining sufficient vine wood, large enough in

diameter and straight in grain from which to make an oud could be a challenge. The biblical reference previously posted implies that it would be

difficult enough to find vine wood large enough to make pegs from let alone anything of larger size. This most likely means that an oud made from vine

wood would have been a rare instrument indeed - hence "only to be found in the treasury of kings".

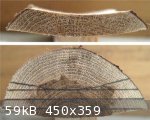

The attached images illustrate the dilemma. The tangled, twisted mass of old vine stems (about 2 metres high) is the material that I am interested in

investigating. The large diameter stems buried in the middle of this tangle may be large enough and long enough to work with - but could also turn out

to be unsuitable. Not only do the stems curve but they also twist. Vines growing up living trees are generally straighter so may be a better choice -

if larger diameter stems can be found.

jdowning - 8-1-2008 at 07:07 AM

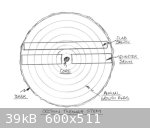

The rib blanks for an early oud with 11 ribs would have measured around 30 inches X 2 inches (760 mm X 50 mm). If the rib blanks were 'sawn on the

quarter', this would require a straight section of vine wood at least 4 inches (100 mm) in diameter. However, if the ribs were "slab sawn" a smaller

diameter vine wood stem could be used.

The attached sketch illustrates the difference between quarter and slab sawn sections for those unfamiliar with this terminology. Either way the core

or pith of the stem is never included. Quarter sawn is the most stable cut as the grain length is minimal and evenly distributed across the rib

section (wood shrinks most in the direction of the cross grain - the longer the grain length the greater the shrinkage). I am not sure if slab sawn

ribs were ever used on ouds (or lutes) but I do not see why not as long as the cuts are made close to the centre of the stem where the grain direction

is still partly on the quarter.

jdowning - 8-1-2008 at 12:25 PM

The Specific Gravity of Vine wood.

This afternoon, the other half of the large sample of grapevine wood was cut to a uniform, squared section, about 5 inches (130 mm) long - on a

bandsaw. The sawn surfaces were then hand planed smooth.

The sample was measured dimensionally using dial calipers (resolution 0.001 inch) and the volume calculated to be 2.985 cubic inches or 48.92 c.c.

The sample was then weighed on a digital kitchen scale (resolution 1.0 grams). The measured weight was 31 grams.

The density of the sample, as measured, comes to

0.634 grams/cc. (I was brought up on the old grams/ centimetre/second and foot/pound/second standard systems - old habits die hard!).

Taking the density of water as 1 gm/cc this gives the specific gravity of the vine wood sample as 0.63. (Density is the weight of a unit volume of the

sample. Specific Gravity is the density of the sample compared to the density of water - a dimensionless number, useful for standardised comparisons

between various materials).

Note that the sample may not be completely 'dry' (moisture content of 8%) - so tests will be repeated on the sample to determine if there has been a

further reduction in specific gravity due to moisture loss. The test could be accelerated by drying the sample in an oven until an equilibrium point

is reached (determined by repeatedly weighing the sample) but, absolute accuracy in determining specific gravity is not critically important - it is

just useful for comparative purposes.

jdowning - 8-3-2008 at 05:47 AM

A second sample of vine stem was cut from a different location in the woodlot yesterday. This sample is 'green' (full of sap), about 2 inches (50 mm)

in diameter and about 21 years old.

The specific gravity of a piece of the sample - prepared and measured the same way as for the first sample - was calculated, in this green state - to

be 0.75. This should reduce significantly as the sample dries out. This sample will also be used to observe how the wood responds to rapid air

drying.

Additionally, two sections were prepared - each cut through the core of the stem - in order to examine the sapwood/heartwood. The sapwood when freshly

cut was white but is turning to a pale brown colour after exposure to light for a few hours. It will be interesting to see if the entire sapwood areas

eventually turn to a uniform brown colouration to match the heartwood. The heartwood is medium brown in colour. In this sample there was evidence of

some localised 'heart rot'.

Both sections showed a pronounced 'ray fleck' or 'cross silk' figuring - particularly in the sapwood, as can be seen in the attached image.

According to one observer, grape vine wood is very brittle when dry. This will be another physical characteristic to verify as the wood may also

become harder and stronger and more resonant (as well as lighter in weight) when dry - which could be desirable for instrument making.

carpenter - 8-4-2008 at 09:28 AM

It's probably not got anything to do with "real" vine wood, but there's something here in W Oregon called "vine maple." It looks a lot like other soft

maple to me when cut, but it grows in multiple stems vs a single trunk. I've seen it on signs on the firewood guys' pickups - "Vine, seasoned." It

could be that "vine" was some colloquial term at the time way back when, for some wood that grew in that vine-y way.

And when it comes to light wood for bowls, I made a bowl from alder, pretty soft for a hardwood, and darn lightweight. Sounded great. My opinion is

that people will trip over themselves to buy an instrument made from fancy, figured hardwoods, even when it's not necessarily in their best interests

to do so. Yet another opinion is that the bowl contains an air volume in a particular shape, and is generally acting as a reflector; it shouldn't make

all that much difference what it's made of, as the top is doing the real work. (If I'm horribly wrong here, and I could be, I figure I'll get

corrected - and soon.)

Meanwhile, I await results on the grapevine. Looks like an interesting experiment. The flecks are a nice feature ...

jdowning - 8-4-2008 at 12:37 PM

Hard to say if the 'Vine' referred to in the early Arabic thesis is 'Grape Vine' - but the latter most likely is the vine species referred to as this

would have been most generally available in the Middle East - significant for its wine growing regions - during the 15th C and earlier?

Farmer translates 'mais' as 'vine' - does this mean 'grape vine' or some other species? I don't know.

The early oud makers were certain that the wood used for an oud bowl did make a difference - the best woods "having qualities which do not exist in

other woods". They do concede, however, that "if these woods (i.e. beech, elm, walnut and vine) are unobtainable, others may be used but they are not

so good".

Thin, lightweight construction referred to as important by the early oud makers dictates the use of woods that are up to the task structurally - i.e.

hard, medium density and close grained. 'Grape vine' - with a specific gravity of about 0.6 (yet to be confirmed) - is not a 'light weight' wood -

but is equivalent to beech, elm, and walnut in this respect.

jdowning - 8-7-2008 at 02:18 PM

Thomas Mace, writing about the lute in 1676 says

" there are very good lutes of several woods: Plum-tree, Yew, Rosemary-air (a maple variety?), Ash - Ebony, Ivory etc. The two last (though most

costly and taking (i.e. pleasing) to the common eye) are the worst". So Mace is confirming that the very dense - and exotic - materials, like Ebony

and Ivory - are not the best for making lute bowls.The same would seem to apply to early ouds?

Just for interest, I weighed two of my lutes, made many years ago - copies of 16th C. lutes. The first (late

16th C, seven courses) weighed in at about 1.6 pounds (0.72 Kg), fully strung and the second (a larger, early 16th C, six courses) weighing about 1.8

pounds (0.81 Kg). I cannot remember how thick I had made the sycamore ribs of the bowls of these instruments - most likely around 1/16 inch (1.5 mm)

but perhaps a little heavier. A target weight for a lute of this period, with thinner ribs,would be around 1.5 pounds (0.68 Kg) I would guess.

Thinness = lightness.

I recall a past quote - but am unable to validate the source from memory - that a good lute is so light in construction that it 'trembles' (i.e.

vibrates) in the hand at the mere sound of a human voice.

The first sample of wild grapevine wood seems to have now stabilised in weight, with some slight shrinkage in dimensions due to loss of moisture. This

sample is mostly heartwood and was quite dry to start with as there are no shrinkage cracks (checks) following the recent moisture loss and shrinkage.

Recalculating, the Specific Gravity is confirmed to be about 0.62. Ambient humidity levels have remained around 70%+ for some time now so there might

be further slight changes as humidity levels drop but not much.

The second sample - about 50% sapwood/50% heartwood and 'green' (live and full of sap) - is a different story. A lesson in how not to season wood!

More to come.

SamirCanada - 8-8-2008 at 04:50 AM

yes please more to come

jdowning - 8-8-2008 at 12:49 PM

........ sample 2 was cut on 02 August from a live section of vine growing up a tree. Sample 1 contained mostly heartwood (from a rootstock stem cut

at ground level) whereas sample 2 contained a significant proportion of sapwood. It may be that vine "suckers" (like sample 2) contain more

sapwood.

Sample 2 was prepared by planing all sides square (dimensions 1.185 X1.354 X5.022 inches) which weighed

99 grams. The sample was left to dry naturally - just to see what happened. Not surprisingly - after 6 days the weight reduced to 78 grams due to

moisture loss and the sample split or 'checked' badly as expected. This is a very severe test (even with sustained humidity levels of 70% +) as the

sample, being cut on all six sides, suffers very rapid moisture loss from the exposed surfaces. This is not the way to season freshly cut 'green' wood

- especially wood with a high sap content like vine!

Another section of the vine was cut through the centre and left to dry over the same period. This section suffered circumferential distortion due to

shrinkage along the growth rings but without any radial shrinkage cracks (as seen in the section alongside in the attached image).

This test confirms that the best approach to preparing vine wood will be to cut the vine in Winter - when the sap content is at a minimum level - then

to coat the exposed ends of the vine with latex paint or wax (to seal the wood pores and limit moisture loss). To accelerate the 'seasoning' (drying)

process without causing cracking - the sections may then be cut through the centre and, temporarily, tied together until seasoning is completed

(determined by weighing each section until the weight is stabilised).

jdowning - 8-8-2008 at 01:49 PM

For information - R. Bruce Hoadley in his excellent and informative book "Identifying Woods" (The Taunton Press), briefly mentions grape vine in a

chapter on 'A-typical Wood' including a nice micro photograph of a Grape vine wood section with its relatively large, ring porous, early wood and

closely spaced, very small, latewood. (compare with image previously posted on this thread).

Hoadley mentions that 'Wisteria' vine (sample dimension about 3 inches in diameter) has a similar ring porous structure to grape vine.

GeorgeK - 8-8-2008 at 05:47 PM

Excellent Post and very thorough!! Thanks for sharing.

Those are some pretty big vines. I dont think I've ever

seen any grow that big in my part of Canada (Ottawa).

I look forward to more of your posts!!

jdowning - 8-9-2008 at 11:31 AM

I am located just East of Ottawa so it is almost certain that wild grape does grow in the rural areas around the city. As far as I can determine wild

grape (several varieties) is native to most parts of the U.S. and Canada. The largest vines would most likely be found in old farm fence lines and

woodlots where they have been allowed to grow undisturbed for decades.

Another source of grape vine might be in the wine growing regions of the continent. Cultivated vines on original root stock can be productive for over

100 years so vines of this age would be quite large in diameter. Vines from grafted rootstock last only 40 years or so by comparison although it is

likely that most commercial vineyards nowadays will be working with grafted vines to avoid the danger of losses due to viral infection and disease.

For comparison, the attached image shows sample 1 after air drying. It is mostly heartwood and the vine had been severed some time ago so this sample

was fairly dry to start with.

The half section of the stem - like sample 2 (but less severe) - shows some convex distortion of the cut surface after drying or seasoning. Annular

growth rings are a series of moisture containing cells arranged side by side in circles of increasing diameter for each year of growth. When wood is

dried, moisture is lost from the cells which then shrink in size - the more cells in a growth ring the greater the amount of shrinkage of the ring. So

the outer growth rings shrink more than the inner growth rings which results in the concave distortion of the cut surface after seasoning.

Half sectioning is a technique that may be used in the seasoning of small diameter logs as it minimises the risk of radial cracking due to built up

stresses caused by too rapid drying.

jdowning - 8-15-2008 at 05:41 AM

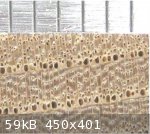

For information and to further illustrate the distortion that occurs due to shrinkage along the grain of the growth rings, the attached image shows

another section of sample 2 that was slab cut when 'green' and allowed to air dry. Note the relatively little distortion in the central slice (quarter

sawn, short, equal length grain) compared to the outer slices (slab sawn, longer, unequal length grain).

The upper surface of the half section alongside was originally sawn flat when 'green'. Shrinkage is greater along the outer rings than along the

shorter, inner rings - hence the curved upper surface after air drying.

jdowning - 8-19-2008 at 11:42 AM

Quote <grape vine wood is very brittle when dry>

Now that I have some well dried samples to hand it is time to check this out.

A strip measuring 20mm wide by 140mm long and 2mm thick was prepared from the heartwood of Vinewood sample 1.

It was possible to easily 'cold' bend this strip into almost a circle without the wood fibres fracturing. Far from being brittle the wood is very

pliable (but not surprising perhaps, given the sinuous nature of the vine plant). This would make Vinewood a good material for basket making, no

doubt, but will it be suitable for making an oud bowl? Much too flexible perhaps?

The next test was to hot bend the strip - with the bending iron at a temperature hot enough to scorch the strip. The strip was easily bent at this

temperature to a bow shaped curve of 30mm radius. On cooling, the strip was found to be much harder and stiffer and held its 'set' well without

'spring back'.

For comparison, test strips were prepared from Ash, Yew, Beech, Elm, Maple and Walnut - all woods mentioned as best for either oud or lute bowl making

in early texts.

To check the relative pliability of these samples, a strip was held (at each end) between the thumb and forefinger of each hand and forced into a bow

shape until it was judged that the strip was about to break. The deflection at the centre of each piece was then measured. Measured deflections were

as follows : Ash 38mm; Yew 32mm; Beech 32mm; Elm 29mm; Maple 26mm; Walnut 19mm. Each sample was then hot bent into a bow shape - at scorching

temperature - to a radius of 30mm. After cooling, the samples were tested for relative 'stiffness' by pressing each end together and comparing the

force required (by 'feel'). The hot bent Vinewood sample was judged to be fairly close in stiffness to the Ash, Yew, Beech and Elm samples. Both Maple

and Walnut were harder to hot bend and a lot stiffer after bending.

It is concluded - from these rather rough, subjective trials - that Vinewood, although it is much more pliable than the other wood species under test

(when 'cold bent'), became significantly hardened with heat to a degree that would make it viable as a material for oud bowl ribs or staves.

Now to make an oud bowl from the stuff! Next year perhaps - after collecting and seasoning sufficient Vinewood.

patheslip - 8-20-2008 at 06:17 AM

jdowning

Congratulations on a well thought out research programme. I admire your persistence immensely.

jdowning - 8-20-2008 at 03:25 PM

Thanks for your interest and kind words patheslip.

Yesterday's trials raised a few more questions that need to be addressed.

The hot bent sample of vinewood was tested to destruction by squeezing the open ends of the sample together. It failed by sudden, brittle fracture

well before the ends met - so the hot bent sample was a lot harder/stiffer than when it was just air dried and subject to cold bending.

Question 1 - how 'dry' was the vinewood sample under test?

Question 2 - did the scorching of the hot bent vinewood samples result in a hardening of the samples?

To investigate further, the original sample 1 (mainly heartwood) and sample 2 (about half heartwood/ half sapwood) were oven dried to remove any

residual moisture after a few weeks of air drying. At the same time a second strip of heartwood (from sample 1) was prepared for testing - to be oven

dried together with the test samples #1 and#2.

Oven drying of the samples (and the second test strip) was undertaken in a microwave oven (when my wife was absent!). Set at 60% power for 1 minute

periods, drying was repeated until the measured weight of each sample became stable and uniform - at which point each sample was assumed to be 'bone

dry' or devoid of moisture.

When freshly cut, the initial measured moisture content of sample 1 was about 29% and about 55% for the 'green' sample 2. After 20 days air drying,

with relative humidity levels fairly constant at around 70% +, the moisture content of sample 1 had dropped to around 12% which was the moisture

content yesterday of the first test strip prior to hot bending.

The 'bone dry' second test strip was found to be just as pliable as the partially air dried vinewood strip in yesterday's trial - from which it may be

concluded that complete moisture removal alone does not result in vinewood becoming less pliable or hardened. It was the scorching heat applied during

the hot bending process that 'tempered' or hardened the vinewood.

Flame hardening of wood is a technology used by "primitive" early civilizations to harden sharpened wooden arrow and spear heads (a method still

recommended in USA army survival manuals).

The attached image shows the brittle fracture failure of the hot bent vinewood sample of yesterday and the pliability of the 'bone dry' oven dried

second test strip of today - for comparison.

The oven dried samples now provide data from which to

re- calculate the specific gravity of vine wood - to follow next.

jdowning - 8-21-2008 at 03:37 AM

The previous posting has been edited, primarily to correct errors in the measured/calculated moisture content of the samples under test and to make a

few changes to the text for clarity.

To summarise, the main observation, according to these most recent tests, is that vinewood retains its pliability even after oven drying to remove any

free moisture. However, after hot bending at temperatures sufficient to scorch the surface of the wood the wood loses its extreme pliability and

becomes hardened and stiffer. So it might be assumed that the high temperatures experienced in hot bending the sample alters the chemical/physical

structure of the cells of the vinewood in some way - sufficient also perhaps to drive out any residual moisture locked within the cells that might be

responsible for the pliability of the wood.

It should be noted that these tests involved accelerated drying methods in order to obtain quick results. It is possible that similar

chemical/structural changes in the cell structure might be achieved naturally by simply seasoning the vinewood for a year or two in the traditional

manner? Time will tell!

jdowning - 8-22-2008 at 12:47 PM

To complete this part of the investigation - pending such time as a sufficient quantity of vine wood can be collected to be seasoned and made into an

oud bowl - here is a better estimate of the specific gravity of vinewood under test. Specific gravity is generally directly related to the hardness

of a wood so is useful for relative comparative purposes.

The Forest Products Laboratory of the U.S. Department of Agriculture handbook, 'The Encyclopedia of Wood', is a comprehensive reference about

domestic species of wood in the USA and its properties.

The Specific Gravity of a wood may be defined as the weight of a wood sample when oven dried divided by its volume at a specified moisture content

compared to the density of water. For moisture content below about 30% (the lower limit for green wood), if the specific gravity is known at a certain

moisture content, its S.G. may be determined by extrapolation at any other moisture content. The specific gravity based on an oven dry weight standard

does not change for moisture content above 30%.

Using this standard to calculate the S.G. for the two samples of vinewood under test, it was found that Sample 1 had an S.G of about 0.50 (this sample

was assumed to be 'green' at moisture content of about 29%) and Sample 2 an S.G. of 0.49.

Extrapolating to a lower moisture content of 12% (air dry lower limit) - using the conversion charts in the U.S. Forestry Service handbook - gives a

specific gravity of about 0.54 and at 8%, about 0.55.

Wood is a variable material so specific gravity might range by 5% plus or minus from an average value for domestic species but can be a much wider

variable for tropical hardwoods.

For comparison here are some wood specific gravities based on the oven dry standard at 12% moisture content.

English Sycamore 0.47 to 0.51

Sugar Maple 0.63 to 0.66

European Beech 0.61 to 0.67

White Ash 0.57 to 0.63

Black Walnut 0.52 to 0.58

European Elm 0. 47 to 0.51

Indian Rosewood 0.76 average

Ebony 0.90 average

Mahogany 0.43 to 0.75

Pacific Yew 0.59 to 0.63

Fir 0.38 average

Larch 0.53 average

Engleman Spruce 0.34 average

Sitka Spruce 0.40 average

jdowning - 8-26-2008 at 05:45 AM

" We'll lounge beneath the pomegranates, palm trees, apple trees, under every lovely, leafy thing, and walk among the vines, enjoy the splendid faces

we will see. in a lofty palace built of noble stones" Ibn Gabirol, 11th C.

This poetic reference is part of the opening sequence of the recent PBS program "Cities of Light" - about Al-Andalus. It confirms that vines were part

and parcel of the everyday lives of Moorish kings and their courts.

Does anyone have access to the original Arabic text - just to verify - from a different source - Dr Farmer's translation of the word "mais" as "vine"?

jdowning - 8-26-2008 at 12:52 PM

A little off topic but, still - almost - related.

This afternoon my wife announced that she had decided to give me her microwave oven "in the interests of science" (Well, actually she wants to buy a

new one to replace it after I have been messing around with it - but that is another story and as basic microwave ovens are quite inexpensive these

days - no problem). I shall use this new found tool to carry out accelerated wood drying experiments - as well as to brew coffee in my workshop. There

is a lot of information 'on line' about microwave drying of wood - particularly among the wood turning fraternity - so it should be an interesting

field to explore further.

I am not a microwave oven enthusiast, however, as the last one that she gave me was promptly converted into a mini 'spot' welder - well, the

transformer was - stripped down and rebuilt. (Warning - never, ever, mess around with the components of microwave ovens unless you really know what

you are doing as the voltages involved (even after the power is switched off) are lethal - a.k.a. instant death!).

Microwave drying of wood might possibly develop into the topic of a future thread.

jdowning - 9-14-2008 at 07:09 AM

Trying to find a better understanding about the identification of the woods in Dr Farmer's translation of the Kitab kashf al-humum, I came across an

excellent website dealing, in depth, with plants of conservation concern to India - a site supported by the Government of India. The data base

includes descriptions of plants identified by both botanical and the (present day) vernacular names in many languages including Arabic, Persian,

Hindi, Sanskrit, English etc.

http://envis.frlht.org.in

None of the names given by Farmer for Beech, Elm, Walnut or Vine could be found in the data base with the exception of "sasam" which is one of the

vernacular names in Arabic for a species of rosewood, Dalbergia Sissoo. This is not the true (East) India Rosewood, Dalbergia Latifolia (Shisham in

Hindi), native to the Bombay region of India, but is today often used as a substitute for Dalbergia Latifolia. The species Dalbergia Sissoo is

distributed as far west as Iraq so, presumably was (and still is) a tree native to Persia.

The alternative words for Walnut given by Farmer (saz and shiz) are likely Persian in origin (?) - saz being the name for the musical instrument and

shiz being the site of Takht-e Soleiman (Throne of Saloman) in ancient Persia, Azarbaijan province. The wood - whatever it was - perhaps being

originally used for making the saz and coming from that region of Persia?

Walnut or Persian Walnut, originated in Northern Persia and was introduced to Europe by the Romans. The ancient Greeks regarded it as a royal wood

which is today reflected in its botanical name 'Juglans Regia' - another wood fit for a king!? The largest Walnut plantation (for nut production) in

the world today is the Shahmirzad orchard in Iran - over 700 hectares in area. Also there are vast Walnut forests covering over 230,000 hectares

further east in Kirghistan. So Walnut is a wood that must have been very plentiful in Persia and the Middle East in ancient times.

The identification of woods by their vernacular name today may not be the same as it was in ancient times - therefore the above does not really

clarify the position. So, what was the basis for Dr. Farmer's translation? Is there a modern dictionary of ancient Persian or Arabic - referenced by

those involved in the study of early languages of the Middle East - where these words, now obsolete in everyday usage, might be found?

jdowning - 9-30-2008 at 04:01 PM

As Fall (Autumn) is now upon us, and the leaves are falling, I have decided to cut some of the more interesting wild grape vine stock from my wood lot

at the same time as I cull dead wood that will be fuel for heating this winter.

The most promising stock is vine that has grown vertically, on a host tree, to produce relatively straight, twist free growth. Some of this stock is

curved but I hope to be able to straighten this and make it viable, during the natural drying process - given the pliability of vine wood while still

'green'.

The vine wood samples in the attached image ranges from 2 inches (50cm) in diameter to over 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter (!).

jdowning - 9-30-2008 at 04:26 PM

The largest diameter root stock (6 inches/15 cm) in the first sample collection is, sadly, useless for instrument making but may be useful for study

in obtaining a greater understanding about vine wood in general. This root stock is badly fissured (radial splits) and, while still alive when cut, is

suffering significant heart rot. In other words, this stock is at the end of its life cycle. Most dramatically, the vine is twisted, beautifully, like

a rope.

I shall section, and determine the age of this sample after preliminary drying.

jdowning - 10-2-2008 at 07:20 AM

The largest diameter vine stem has been sectioned and planed smooth to reveal the annual growth rings. A ring count indicates that the age of of the

stem is about 60 years - estimating the rotted out section of the stem as representing about 10 years of growth.

The reference scale in the attached image of the sectioned stem is 6 inches/ 15 cm.

Comparing ring counts with the smaller diameter

(2 inch/5.0 cm - 20 years old) vine samples confirms a growth rate of about 10 years per inch of stem diameter for wild vine grown in this

locality.

jdowning - 10-3-2008 at 12:07 PM

This is a pleasant time of year to be walking through the woods and in doing so today I found another three promising looking vine stems - fairly

straight and about 2.5 to 3 inches (64 mm to 76 mm) in diameter. These will be cut tomorrow.

Planning ahead - the vine wood will eventually be used to build a replica of an early 5 course fretted oud (subject of a new topic) - if I can find

sufficient stems of appropriate size and free of significant flaws. The design will be based upon the oud geometry described in the topic "Analysis of

an Early Oud Woodcut" on this forum. This design would appear to be the earliest (and most fundamental) geometry of an oud on historical record.

Choosing an arbitrary (but comfortable for me!) string length of 60 cm for this proposed instrument gives a rib blank length of about 25 inches (635

mm). Rib blank width for a (preferred) 11 rib bowl would then be about 2.1 inches (53mm) or about 1.8 inches (46 mm) for a 13 rib bowl. These

calculated dimensions now give me a target for selecting, cutting and preparing the vine wood stock. This means that - given the limited diameter of

the available vine stems - the rib blanks will be slab sawn.

carpenter - 10-3-2008 at 01:12 PM

That twisted piece is something! I had a 6" dia. limb of plum wood once that spiraled for one turn in a foot for quite a ways up the stick; turned out

to be useless for my needs at the time, but it was a nice conversation piece on the mantel. I couldn't count the rings even with my glasses.

Some Ancient told me fruitwood generally has twisting/spiraling tendencies. Dunno. Could be so; I haven't had enough of it around to tell. Fruitwood's

lovely turning wood when it's straight and behaves.

Interesting posts as usual, and good luck with that vine wood.

jdowning - 10-4-2008 at 11:58 AM

Thanks Jim. I think that the 'wild' spiral twisted sample of vine should be converted into something 'useful' - like a pencil holder - by boring out

the dead centre and mounting it on a wooden block - not only to preserve it as an unusual conversation piece but as a little piece of history, given

that this vine started life just after the end of World War 2.

I gathered some more vine wood today - the largest being over 3 inches in diameter and about 10 ft long and fairly straight (growing vertically up a

tree. There is more further up but I could not reach it without a ladder). The cut ends of the vine sections collected have all been coated with latex

primer paint to protect against checking (splitting) of the ends due to too rapid drying.

It is inevitable that there will be some degree of twist, local knots and grain 'run out' evident in all rib blanks made from this material. I am

hopeful, however, that the natural flexibility of the vine - previously reported - will allow manipulation of the wood during the natural drying

process to minimise the effect of these natural 'flaws'.

No guarantee that any of this will be successful at the end of the day. Worth a try though.

carpenter - 10-4-2008 at 12:22 PM

<< coated with latex primer paint to protect against checking (splitting) of the ends due to too rapid drying. >>

I had bad luck with latex once upon a time; either it wasn't thick enough or I just messed up, checks galore. I subsequently got great results (with

different wood) with melted paraffin, or "canning wax;" the white stuff. A dip or two did the job. A friend of mine globbed on some aluminum paint on

some oak, and had good results ...

If anybody is drying green wood, the water goes out the ends at a much higher rate than through the sides, so sealing the ends is key - with a capital

Sealing - to minimize checking. Stickers and shade-drying are also good; slow and steady.

Josh - how's drying that nice apple wood going (if you're reading this)?

jdowning - 10-5-2008 at 04:48 AM

I am using two coats of latex primer to seal the end grain during drying. Primer is a lot thicker than latex top coat paint as it is essentially a

wood sealer. It should be OK for this application and is also 'compatible' with moisture in the freshly cut wood. Paraffin wax will do as well but has

to be melted and is a more fragile coating (tends to break and peel off if knocked accidentally) I have found.

Alternatively, paper glued over the end grain surfaces can be used.

Nevertheless, it is always best to leave extra material at the end of the sawn boards so that any end checking that inevitably might occur can be cut

away after the wood is fully dried.

jdowning - 10-6-2008 at 12:48 PM

The freshly cut 3 inch diameter stem was cut 48 hours ago and the cut ends painted with latex primer. Yesterday I noticed that the primer had not

dried. Cutting the stock into "straight" sections for converting into rib stock (hopefully!), the sap suddenly started to flow from the cut ends with

a steady 'drip'. Left overnight, with the cut lengths stacked vertically to allow drainage of the sap, the copious sap flow has congealed into a

'jelly like' consistency as shown in the attached image.

Not sure what is going on here but it may be that this is some kind of protective mechanism by vine wood to seal broken stems and ensure continued

healthy growth. Perhaps, artificially, sealing the cut ends, in this case, may not be necessary? So, although grapevine essentially has the cell

structure of a wood it is also 'plant like' (i.e. not 'tree like') in some ways. However, note that some species of wood like sycamore (a kind of soft

maple) when freshly cut - the boards must be initially stacked vertically to accelerate (presumably) initial sap drainage to minimise undesirable

staining of the wood due to retention of the high sugar content sap of the species.

Once this excessive sap flow has ceased, the relatively 'dry' cut ends will be re-coated with latex primer to seal against further rapid moisture loss

to minimise checking.

Nobody said that this was going to be easy!!

SamirCanada - 10-6-2008 at 02:56 PM

Ha! neat...

jdowning - 10-8-2008 at 12:34 PM

Before I forget - for some unknown reason (to me) this seems to have been a very bad year for wild grape on my property with hardly any fruit in

evidence. Not sure if this will have any bearing on this investigation but worth noting nevertheless.

Once the vine stems have been cut to the required length, drained of sap and the partially dried cut ends coated with latex primer, they will be left

to dry further under cover for a couple of weeks or so.

The strategy for cutting the stems into slabs for seasoning into rib blanks will be first to cut each stem in half longitudinally - following the

irregular grain direction as closely as possible. This means, for example, that stems that are curved will be cut in a curve. The curved strips will

then be straightened out, during the seasoning process, by placing them under load in a drying frame. More on this later.

Any soft pith in the centre of the half sections will be cut away at this stage to reduce the risk of heart shakes developing (radial cracks caused by

too rapid drying starting from the central pith).

The attached image shows an example of heart shake in one of the vine samples described earlier in this thread. This sample is a stem 2 inches (50 mm)

in diameter and about 20 years old. The crack is about 8 mm long radially and extends only about 13 mm deep into the stem from the cut end - so is not

as serious at might first appear. This stem had been allowed to air dry without any coating being applied to the cut ends - so has dried a little too

rapidly. An end coating applied at the start of the drying process would most likely have prevented or minimised this fault.

jdowning - 10-8-2008 at 05:11 PM

As noted in an earlier posting, if a horizontal slab is sawn through a section of vine when it is 'green' and then allowed to air dry, the slab will

dry, naturally, into a curved profile. This is because the wood shrinks (in section) along the 'grain' of the growth rings - the longer the grain

length, the greater the degree of shrinkage. This can be seen in the attached upper image of a slab sawn section from one of the samples previously

posted. This example is a typical slab sawn section with most of the grain running - more or less - across the width of the slab.

Cutting the vine stock in this manner, while still 'green', will further minimise the risk of checking or cracking of the section during the drying or

seasoning process by reducing the stresses involved.

In order to saw rib stock from the slabs, after drying is complete, allowance has to be made for this predictable distortion of the wood. The lower

image shows how rib blanks may be sawn from the dry but distorted slab - the upper and lower curved surfaces first being planed level and the dressed

slab then being sawn in two (if there is sufficient material thickness remaining). In this case (for a 2 inch diameter vine stem) a slab initially

measuring about 1/2 inch (12 mm) in thickness when 'green' should be sufficient to provide two rib blanks of adequate width and thickness when sawn.

This equates to four rib blanks per stem. Larger diameter stems should provide even more rib blanks of greater or equal width.

Note that rib blanks cut in this manner would have a grain direction somewhere between 'slab' and the 'quarter' sawn ideal.

So, this is the planned strategy for dealing with small diameter vine stems. Time will tell if it succeeds or fails!

jdowning - 10-13-2008 at 12:29 PM

The wild vine collected so far has been cut into lengths of about 28 inches (72 cm) and the loose fibrous bark stripped off. Stripping the bark

revealed hidden severe faults in some of the vine samples like deep fissures and extreme twisting. Also, many of the samples suffered from heart rot.

All of these faults make the wood useless - well, only good for burning.

Of all the samples collected, the 3 inch diameter stems are the most promising but less than ideal as none of these are straight grained but curve and

twist to a certain extent. In light of this, I have decided to slab cut these sections along an 'average' two dimensional plane which means that the

sections cut from this stock will be curved. However, as oud ribs taper from end to end, I am hopeful that - given the width of the sawn stock (3

inches max.) - that there will be sufficient scope to produce ribs of adequate dimensions from this curved

slab cut stock.

The 3 inch stems are still very 'green' so I do not want to leave them in this state for very long before re-sawing them into slabs for drying

(seasoning), in order to reduce the risk of checking (splitting of the wood).

To re-saw the stems, a simple carriage was built to hold the stem safely and securely while being sawn in a bandsaw. My carriage was made from a piece

of scrap 3/8 inch (10 mm) thick plywood screwed to a 3/4 X 2 inch wide (19mm X 50mm) pine base. All very 'rough and ready' but good enough for the

job.

Each section of vine stock was mounted in the carriage in a vertical plane (all done 'by eye' - a 'judgement call' for each piece) and then cut in

three pieces by making a central cut on each side of the heart of the stem - about 1/2 inch(13 mm) thick.

The attached image shows a stem firmly secured to the carriage (with short, drywall screws) in the process of being re-sawn on the bandsaw.

jdowning - 10-13-2008 at 12:40 PM

The attached image shows the stem cut into three pieces ready for seasoning.

The grain pattern of this stuff is - well - 'wild'!!

Interesting times ahead.

jdowning - 10-14-2008 at 07:12 AM

ALAMI has uncovered some interesting information that puts Dr Farmer's interpretation of 'mais' as meaning 'vine wood' into question and which seems

to me to be a more likely candidate than vine might be.

I shall leave it to ALAMI to pick up this thread and go into detail about what he has found.

Mais part 1

ALAMI - 10-14-2008 at 08:24 AM

I met an old carpenter few days ago and asked him if he heard of Mais and he answered: "of course it is the wood from the Mais tree, the old trees of

Mais Al Jabal"

I missed the link completely when John wrote about Mais, "Mais Al Jabal" (Mountain's Mais) is a village in southern Lebanon known for his old trees,

there are also many villages in the Golan that have a name starting with Mais, There is even a famous musical play of Feiruz (the Lebanese diva)

about an imaginary village called "Mais El Reem".

It seems that Mais trees can be very old and they have the power to protect against witchcraft, people consider them sacred and never cut them, they

only take a small piece that they keep on them for protection.

There is also a popular legend about an old Mais Tree in Jerusalem near the Dome that was touched by the prophet and that has great protective

powers

I searched a bit around and found that in Palestine, Mais or Abu Al Mais is used to design cedar ( C. libanotica LK) but not in Lebanon where cedar

is called ARZ and it is also a sacred tree with even a religious day called "cedars of God day" (Aug 15),

Lebanese Cedar was mentioned in the epic of Gilgamesh (the oldest book of humanity) and also in the Bible and old Egypt documents (it was used for the

royal boats).

But is Mais the Lebanese cedar ? not according to the old carpenter, in Lebanon and Syria it is designing the tree that is on the attached images, it

seems also that this tree has small black and sweet fruits.

In old syriac language "Mais" means "Zbib", in modern arabic, Zbib is dried grape raisin but it is also used for any dried small fruit, this might be

the origin of the confusion in Farmer's translation as for him Zbib=Dried Raisin that can only comes from vine which is not the case in arabic use of

"Zbib"

That's what I have on Mais, it is not conclusive but it may be a step towards identifying Farmer's Mais.

The pictures below are supposed to be a Mais tree from a syrian village.

Parrt 2

ALAMI - 10-14-2008 at 08:45 AM

Following "le fil d'Ariane".....

With the above infos as source a further search led to a Bible related website:

http://net.bible.org/dictionary.php?word=botany

where the following text is found:

"The southern hackberry or nettle tree (Celtis australis; Arabic mais) a member of the Urticaceae closely allied to the elm, is an indigenous tree

which is widely planted; it is not uncommonly seen beside Moslem shrines. It grows to a height of 20 to 30 ft., and yields a close-grained timber

taking a high polish"

The result makes sense and is in line with part one,

A second search, now on hackberry and celtis australis revealed that it's a big tree, it has small sweet fruits and the image looks similar to the

Syrian Mais above (but I am not expert in this)

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Ulmaceae_-_Celtis_Australis...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtis_australis

So is Farmer's "Mais" the Hackberry ?

Is Hackberry used in oud or other instruments making ?

jdowning - 10-14-2008 at 12:53 PM

Nice work ALAMI! Thanks for the relevant links.

Interesting that the 'Hackberry' (Celtis occidentalis L) is related to the Elm species. Of the 70 species of hackberry that occur worldwide - mostly

shrubs or small trees of no economic importance - only one occurs in Canada and so I am not familiar with the wood.

Dr Farmer interpreted 'dardar' as being Elm. This also would seem to be an unlikely wood for instrument making in my opinion, judging by the Elm

species that grow locally (i.e. 'White Elm' which is coarse grained and with interlocking grain structure that makes the wood very unstable during

seasoning so that if the boards are slab cut too thin (under 2" or 50 mm in thickness) when 'green' they will cup and twist to become useless for any

purpose after drying).

However, the Old Testament of the Bible mentions dar-dar (in a parable) as being a kind of parasitic thorn tree that eventually kills the host tree

(like grapevine) - so is, perhaps, another unlikely wood (like vine) for instrument making?

This opens up a whole question about what woods were used to make early ouds (and lutes). To add to the problem, vernacular descriptions of a wood in

one region of the world may apply to a quite different species of wood in another region.

I have always thought (not quite sure why and from what historical source) that early ouds were often, typically, made from walnut and mahogany but

now need to question this assumption.

In the meantime! - I shall proceed with preparing some samples of vine wood veneer, possibly for making into an experimental oud bowl - or just as a

very rare wood sample to test out the knowledge of local wood 'experts' - just for fun!

ALAMI - 10-14-2008 at 01:44 PM

John, his wood investigation you launched across time, translation and languages is a real jungle.

Arabs usually disagree on many things and, now that I am looking into this, it seems that there is a different name for each tree in each region and

each period.

Al dardar is in fact Elm and it is originally a persian word, but this is true only for modern times because in old Arabic (the period of the

manuscript) Dardar used to mean Ash.

Regarding Al Zan, it is beech but it seems that it is also sometimes used for Fir.

Yeah, I am lost too.

jdowning - 10-14-2008 at 05:08 PM

Thanks for the additional, helpful information ALAMI.

'Figured Ash' was certainly used for early 16th C lutes. The commonly available Ash wood in my part of the world (White Ash) is, however, in my

opinion, less suitable for instrument work being fairly coarse grained and rather plain in grain structure (but a very useful material otherwise).

Wood is a very variable material!

So, if I want to try to recreate an early (circa 14th C) oud, what wood species should I choose for the bowl? Very difficult to know under the

circumstances.

My old Egyptian oud, currently undergoing restoration, I have assumed is made from Walnut and Mahogany - but now I have doubts. I shall take a closer

look at the cell structure of the (replaced) damaged peg box back plate to try to determine and confirm the wood species.

jdowning - 10-15-2008 at 12:34 PM

A bit more information about the single species of hackberry tree found in this part of Canada - from the Canadian Forestry branch book "Native Trees

of Canada". It is a 'small' tree 25 to 60 ft (7 to 18 meters) in height and up to 2 ft (60 cm) in diameter. It looks like an elm - and is often

mistaken for an elm - with a large bushy crown of ascending branches often flat topped and spreading. This species is found in the St Lawrence and

Ottawa Valleys but is not common anywhere in Canada. The tree carries a fruit - berry like and dark purple - about 1/3 inch (8 mm) in diameter with

edible flesh and hard kernel. The bark of the tree is greyish-brown and ridged. The leaves are lance shaped (pointed tip) with serrated, 'saw like'

edges.

Bruce Hoadley ('Identifying Wood' - Taunton Press) compares this species of hackberry to 'slippery elm' a native 'soft' elm species with similar cell

structure.

I have never seen a mature specimen of the hackberry tree locally but will now keep my eyes open to try to find one.

I shall next post a scanned image of the leaf, bark and fruit of the Canadian species of hackberry for information and to help in identification of

the tree.

SamirCanada - 10-15-2008 at 01:29 PM

Ok so all this research into vine is not wasted after all.

especially if you make a oud out of it John!

I got scared that all you had done so far was down the trash.

Interesting subject fellas. keep up the good stuff!!

jdowning - 10-15-2008 at 02:15 PM

Nothing is wasted Samir. If it can be proven that Dr Farmer had mis-interpreted the original manuscript and incorrectly identified 'mais' as vine

wood, then this may be important progress in researching the history of the oud that otherwise may never have come to light. As ALAMI has indicated,

positive identification of the woods described by the authors of these centuries old texts may be difficult, if not impossible, to determine with

certainty today. Not that we should not try. So, Farmer may still be correct - but, nevertheless, I think that ALAMI's alternative interpretation is

convincing. All 'grist to the mill' in the quest for historical truth!

As for the vinewood I intend to press on in preparing my collected samples for use, after seasoning, as the wood - even if eventually proven not to

have been used in early ouds - is sufficiently interesting in its own right to warrant continuing further investigation.

ALAMI has suggested that the 'mais tree' might be a species of the hackberry tree. The attached image shows some characteristics of the hackberry tree

(Canadian) that may help in positive identification of the tree elsewhere. Grid scale is

1 inch or 25.4 mm

jdowning - 10-16-2008 at 06:02 AM

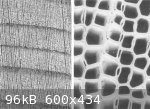

The attached macro images of American Elm (Ulmus americana) may help further in identifying Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) which has a very similar

cell structure to the Elm family of woods. Elm and Hackberry are identified by the characteristic wavy bands of the latewood cells (the small diameter

cells). This arrangement cells is known as ulmiform, from Ulmus (elm).

The earlywood cells (the large ones) in the American elm sample shown here are characteristically arranged, more or less, in a single row whereas in

hackberry the early wood is more than one pore wide - as also found in Slippery Elm (Ulmus rubra). Both hackberry and elm are ring-porous woods.

To distinguish between hackberry and elm, the heartwood of hackberry is coloured cream to light brown or yellowish grey whereas the elm heartwood is

brown to reddish brown. Also in hackberry the radial 'rays' can be up to 10-12 cells wide with some always wider than 7 cells whereas in elm the

largest rays are generally 4-5 cells wide but never wider than 7 cells.

(Information from 'Identifying Wood' by Bruce Hoadley)

jdowning - 10-16-2008 at 06:37 AM

This image shows the cell size of the American Elm sample - the reference scale is in millimeters.

For information, this sample of elm is from my woodlot. It is a very common tree subject unfortunately to elm disease that kills a number of elms each

year. I burn a lot of small diameter dead elm for winter stove wood. Larger trees (up to 30 inches or 76 cm in diameter) may be slab cut with a

portable chainsaw mill into boards 2 inches or more in thickness for air drying and use as timber. I have quite a quantity that has been drying for

years. So the good news is that I have plenty of elm from which to select rib stock for making early oud replicas - if we can be reasonably sure that

this wood may have been used in the past.

As for confirming that the Mais tree in the images posted by ALAMI is a species of Hackberry, it will be necessary first to obtain a sample of the

wood (a piece of a small diameter branch or twig) and examine the grain structure with a 10X magnifying lens. Also to examine the leaves, fruit and

bark.

To prepare wood specimens for examination of the cell structure I simply smooth the cross grain section with a sharp, low blade angle plane to produce

a clean cut. For small sections of wood a single edge razor blade may also be used to produce a clean cut across the grain. The images were taken with

a Canon A470 digital camera. This is described as an "Entry Level" camera but is sophisticated and versatile and relatively low cost (around $130).

One, of many reasons that I chose this model was because of its super macro, close up facility as evident in the images posted. The posted image files

have been considerably compressed in size so some detail and crispness of the original images has been lost.

jdowning - 10-16-2008 at 12:33 PM

The last stage of preparing the vine wood samples for seasoning is to 'sticker' each three piece section. 'Stickering' means placing strips between

each cut layer to allow air to circulate and allow drying of the wood. Each length of vinewood stem has been 'stickered' with strips of spruce about

3mm thick at each end and in the centre and the whole lot bound tightly together with three double loops of 14 gauge wire tensioned - like a

tourniquet - with a metal rod.

The sections will now be stored in a granary loft to dry over the coming winter period.

This is a seasoning method that might be used for small diameter logs of other wood species.

ALAMI - 10-16-2008 at 12:53 PM

John, just allow me to say that you have this talent of making any subject you approach interesting and inspiring, your curious, scientific, open and

yet passionate mind is an inspiration.

I learned and still learning a lot from you and I am sure that most of the guys here think the same... thank you.

Back to wood,

I asked someone to give a look to an arabic botanical encyclopedia and here's what I got:

- Sayam is also called SAJ or SAG and it seems that it was always imported from india and was also used for boats and weapons.

- Al Dardar in old arabic is "Flowering Ash" that is Fraxinus ornus L very common in the Middle East

- Al Zan is beech

Mais is still the most mysterious one,

As Samir said, we are all eager to see this investigation, along with the "old woodcut" and the one on glue transform into the first replica of a

medieval oud by John Downing.

jdowning - 10-17-2008 at 12:45 PM

Thank you for your kind words ALAMI. I also have learned a lot since joining the forum and will continue to do so thanks to the interest of

contributing members. It is a pleasant and fulfilling journey of discovery for me. So the sentiments are very much reciprocal. Thank you!

My first oud (or two) will be a recreation of a medieval oud (from the 'woodcut') - based upon the best research data currently available - thanks to

this wonderful forum. Subject of a new topic for next year.

Just for information, a slight diversion mentioned earlier in this thread and while on the subject of identifying wood species by cell structure - the

damaged pegbox backplate of the old oud that I am currently (very slowly!) restoring - that I thought might be Mahogany - has been microscopically

examined and compared to the data and images in Bruce Hoadley's book. This is a very small sample (about 2 mm thick) and I am an absolute beginner

(but eager to learn) in this fascinating field of wood identification. The backplate would seem to be very close in cell structure to 'Central

American Mahogany' (Swietenia spp) as defined by Hoadley.

The attached image of the end grain of the back plate has been rotated so that the radial rays are vertical. Not the clearest of images but note the

distinctive tangential rings and cells containing dried red gum deposits which may distinguish this from African Mahogany (Khaya spp)

jdowning - 10-22-2008 at 05:18 PM

Dr Farmer also mentions another wood used to construct ouds in his translation of the 14th C Persian manuscript Kanz al-tuhaf .... "The best wood for

this purpose is 'shah' which comes from Darya-har, although sometimes the wood of Sardia is found good"

Any suggestions as to what woods these might be?

jdowning - 10-23-2008 at 03:54 AM

...... 'shah' meaning 'king of kings' (?). Another royal wood!

Another difficulty in identifying the woods described by these early writers may be in the two stage translation from the original Arabic or Persian

text into phonetic and then into a modern Western language? Much may be lost in the translation so there is probably a need to examine the original

source documents as well - which is always a good idea - easier said than done, however.

Thanks to ALAMI's most recent investigation, one wood that does seem to be consistent in translation is 'Al Zan' or beech wood. This is a wood that I

have seen used successfully by modern day lute makers but not sure if any surviving early lutes were made from beech. Ash was used in early16th C

lutes. Usually fairly plain in its grain pattern, Ash is sometimes found with figuring similar to that more commonly found in Maple - which likely

makes the wood harder than plain Ash (?). As far as I know it is the figured Ash that was used by the early luthiers.

I am not familiar with the 'Flowering Ash' tree or its wood. Popular for ornamental planting in gardens in the West it would seem.

jdowning - 10-23-2008 at 12:49 PM

For information and comparison - now that 'Ash' may be a possibility - the attached images show the end grain cell structure of a sample of White Ash

(Fraxinus americana) from my woodlot (the top image) and Black Ash (Fraxinus nigra) recovered from a floor joist in a demolished local building built

during the 19th C.

Ash is a ring porous species - like Elm/Hackberry - and is quite similar to the latter two species in cell structure except that it does not have the

distinctive 'ulmiform' wave pattern of the latewood cells (although the white ash latewood cells do, somewhat vaguely, join together, in wavy

bands.

I would expect that 'Flowering Ash' (Fraxinus ornus L) would have a similar cell structure to White/Black Ash.

As an aside, I am very pleased with the macro image capability of this, relatively low cost, Canon A470 digital camera (one of my latest technical

'toys') - that can be used (among many other things, including video image recording) as a low power digital microscope. It can see details that I, in

old age, now longer can - even with a optical 10X lens.

jdowning - 10-28-2008 at 12:49 PM

Continuing with more (compressed) macro images of the cell structure of woods mentioned in this thread - just for information and comparison - here is

an example of European Beech wood (Fagus grandifolia).

Beech (and Sycamore) are classified as "Diffuse- Porous" woods. The pores are small and in irregular multiples and clusters evenly distributed

throughout most of the growth ring.

Note that my set up for taking these these digital images is quite 'rough and ready' - the camera simply being pressed firmly to my work bench and

aligned to the specimen by eye, allowing the camera on 'auto' to undertake proper exposure, focus etc. - less than ideal for macro photography where

focus is critical due to lack of depth of field. Also, preparation of the specimens is less than ideal - simply using a sharp plane to prepare the

wood section is fairly inaccurate. So, in these images scratch marks are in evidence as well as some extraneous fibers from paper towels used to wipe

the prepared surfaces. However, although they do not compare in clarity to the photos in the Hoadley book - they, nevertheless give a pretty good idea

of of the typical cell structure of each wood species.

jdowning - 10-28-2008 at 02:01 PM

Walnut - in this case Black Walnut (Juglans nigra). Walnut is classified as Semi-Ring-Porous with fairly large early wood cells decreasing gradually

to quite small latewood cells. Black Walnut is very similar to the European variety (Juglans regia) except that the latter is usually lighter in

colour and lacks the pore size contrast of Black Walnut.

jdowning - 10-28-2008 at 02:15 PM

East India Rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia) - classified as 'Diffuse-Porous" with variable sized cells, large and small, irregularly distributed. Growth

rings indistinct.

jdowning - 1-6-2009 at 01:25 PM

Watching a TV program on New Year's Eve about the great Egyptian pyramid builder Sneferu, first pharaoh of the fourth dynasty (2613 BC to 2589 BC) I

was interested to note that surviving inside Sneferu's less than successful "Bent Pyramid" are some original timbers supporting the cracked ceiling of

one of the chambers. The commentator said that the timbers - over 4000 years old - had come from southern Lebanon.

On investigation, one reliable source confirmed that the timbers were cedar wood and that there were also fragments of a cedar coffin inside the

pyramid.

When ALAMI posted two possible alternative woods to Farmer's 'Vine' - Hackberry and Cedar of Lebanon - I was less than diligent in looking into cedar

as I assumed that the woods referred to by Farmer were all hardwoods used for making oud bowls - which discounted cedar as a possibility in my mind.

However, checking Dr Farmer's translation again there is no such specific use mentioned - so the woods mentioned by him might be either soundboard

woods or bowl woods.

Further research revealed that, Sneferu, from an inscription on the 'Palermo Stone', tells of importing 40 shipments of cedar logs from Lebanon (i.e.

the forests on Mount Lebanon) for making ships and the doors of his royal palace. The Egyptians believed that cedar wood represented eternal life.

Cedar resin and sawdust was used in the mummification process for their kings.

Phoenician king Hiram of Tyre provided cedar logs from Mount Lebanon for the building of the famous temples and palaces of David and his son Solomon -

kings of Judah and Israel - structures with cedar columns, support beams and wall and ceiling panelling. The altar of Solomon's temple (completed in

960 BC) was made from cedar. A main room in one of his palaces was named "The Hall of the Forest of Lebanon".

The recently excavated royal tomb, supposed to be that of Midas, king of Phrygia (late 8th C) at Gordion in Turkey is built in part of cedar logs and

contains a coffin carved from a huge cedar log.

Following a military invasion of Syria, Shalmaneser III (9th C BC) demanded tributes from one prince to be paid in part with two hundred cedar logs.

Another prince had to provide two hundred cedar logs and one hundred cedar logs each year thereafter. A third prince was required to supply three

hundred cedar logs annually.

King Sargon II (late 8th C) regarded cedar timber as a valid taxation payment.

So, the Cedar of Mount Lebanon was a very valuable wood in ancient times - both from a religious and spiritual point of view as well as one that might

easily be found in "the treasury of kings" because of its monetary value.

Not only that, but until fairly recently, Cedar of Lebanon was widely used as a soundboard wood for ouds. Sadly, the Cedars are now in serious

decline, a threatened species - victim of over harvesting and other poor forestry practices as well as environmental pressures.

Given this information, of the three condenders - Vine, Hackberry and Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani), I would now rank cedar as the most likely

translation of 'Mais'.

Cedar of Lebanon is a fairly heavy softwood with a specific gravity of about 0.52. Interestingly Farmer translates 'Sharbin' as 'Larch' wood, an oud

soundboard wood mentioned by

14th C writer Ibn al-Tahhan. Larch is also a heavy softwood with a specific gravity of about 0.52. More dense soundboard woods would imply thinner

soundboards than those made from spruce most commonly used on ouds today.

For completeness the attached macro images show the transverse cell structure of Cedrus libani. (source 'Manual of Traditional Wood Carving', Paul N.

Hasluck, 1911, Dover Publication reprint and 'Nitrogen Cycling by Wood Decomposing Soft-rot Fungi in the King Midas Tomb, Gordion, Turkey', 2001, by

Filley, Blanchette, Simpson and Fogel).

Presumably, Cedar of Lebanon, of a quality suitable for making soundboards, is no longer available? If anyone knows of a reliable source - let us all

know!

jdowning - 1-13-2009 at 12:59 PM

Three more historical references linking Cedrus libani with kings, their treasuries, palaces and temples and the Lebanon.

Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal (883 to 859) left detailed records of logging operations in the Lebanon and Amanus. His men cut four species of trees

including Cedrus libani.

King of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar (605 BC to 562 BC) left an inscription in the Wadi Brisa, (adjacent to the cedar forests of the Lebanon) where he

claims to have built a road and a canal " to carry, like reed stalks, mighty cedars, high and strong, of precious beauty and of excellent dark quality

- the abundant yield of Lebanon ".