| Pages:

1

2

3 |

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

The Turkish Oud Hiatus?

At the present time I am generally ignorant about the history of the Ottoman Empire so am looking for informed information about the Turkish oud that

- today - has distinct characteristics.

Apparently - according to some sources - the oud in the high art culture of the Ottoman court - centred in Constantinople - went out of fashion in the

17th C. Orchestral music then took precedence - favouring larger audiences - a similar situation, it would seem, to the demise of the lute in Western

society in the mid 18th C.

It is said that the oud was later reintroduced to Ottoman Empire during the 19th C - a time of nationalistic sentiment.

Does anyone know what happened to the oud during the 200 years between the 17th and 19th C in Ottoman Turkey?

|

|

|

DoggerelPundit

Oud Junkie

Posts: 141

Registered: 7-28-2010

Location: Pacific Northwest

Member Is Offline

Mood: Odar

|

|

I, for one, have no answer for this interesting question. However, for a good background and possibly some clues, allow me to recommend Music of

the Ottoman Court, Walter Feldman, International Institute for Traditional Music, Berlin, 1996. At around $75 it's expensive, but worth it.

Though Feldman doesn't address your question, there are a couple of tantalizing mentions worth repeating:

Pg. 143, “Only toward the fall of the Ottoman Empire did the Tanbur begin to share its position in art music with another lute, the

‘ûd, which had been reintroduced to Turkey from Syria and Egypt.”

and...

Note 63, page 510, says in part, “…no dervish order in Turkey adopted the kobuz, ikliğ, or kemençe as a sacred

instrument. It may be for this reason that no bowed instrument retained its place in the Ottoman orchestra…Likewise, the secular prestige of the

‘ûd and the çeng did not prevent these instruments from disappearing entirely from the orchestra.

In that last sentence, the apparent distinction between secular and art music is interesting. Does this mean the ‘ûd was in Turkey all

along (18th & 19th centuries) but just not appearing in art music?

-Stephen

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Thank you Stephen.

The reintroduction of the oud from Egypt and Syria in the 19th C - then part of the Ottoman Empire in its decline - is interesting. Does this mean

that during the 'hiatus' period no ouds were being made in Turkey that the master luthiers had moved (for economic reasons) to other regions of the

Ottoman Empire where the oud was still held in high regard?

Were the reintroduced ouds then made to the same luthier traditions and designs as the ouds of former times in Turkey? Impossible to say , of course,

but why is the Turkish oud of today significantly different in size and geometry from ouds in other regions of the Near/Middle east?

|

|

|

DoggerelPundit

Oud Junkie

Posts: 141

Registered: 7-28-2010

Location: Pacific Northwest

Member Is Offline

Mood: Odar

|

|

"...but why is the Turkish oud of today significantly different in size and geometry from ouds in other regions of the Near/Middle east?"

All the sources I have seen point to Manolis Venios (Manol in Constantinople) as having "redesigned" or "recreated" the Arabic sized and tuned ouds

into what has become known as the Turkish style. (If this is so, it would be rather like another Manolis—Manolis Hiotis—who added a 4th course to

the 3 course Rembetic bouzouki and electrified it. In more than one way, I guess).

But your first, and main, question is still in the fog. Who, if anyone, was making and playing ouds inside Anatolia from about 1750 on. And, what was

the form of the "reintroduction"; who was involved?

-Stephen

|

|

|

Danielo

Oud Junkie

Posts: 365

Registered: 7-17-2008

Location: Paris

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Interesting topic !

To bring a modest contribution to this discussion.

In the CD "Les orients du luth - vol. 2" Marc Loopuyt is playing, among other ancient ouds :

TOQATLE ONNIK, Konya 1823

And surprisingly the sound of this instrument is not really turkish (in the way that we mean today), it has a very 'dry' sound, more of the near-east flavor.

It would make sense that what we call today a turkish oud was, indeed, designed by Manol.

Is it also surprising that, in this interesting rendering of 17th Ottoman music, old Nahats, rather than Manol or other turkish ouds of the same period, were used ?

regards,

Dan

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

I have not had time to study in more detail the geometry of the surviving 'Turkish' ouds (including those made by Greek and Armenian makers as they

all appear to have similar profiles).

I would agree that it is very unlikely that the oud disappeared in Turkey during the 'hiatus ' period (between the 1600's until the late 1800's). It

is just that, apparently, the oud just did not have much of a place in the 'high art' orchestral music scene.

I would be surprised, therefore, if the oud - when it regained popularity in Turkey during the 19th C - was an instrument that was reinvented by

Manol. The problem, of course, is that no ouds survive prior to the 19th C so we cannot know for sure about the geometry of pre 19th C ouds for

comparison.

So where does the claim that Manol is the inventor of the modern Turkish oud originate?

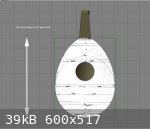

The attached image of a 'traditional' Turkish oud geometry indicates that it was based upon a 3:4:5 'Pythagorean triangle in defining the upper sound

board profile - as were the Nahat ouds (as well as many lutes of the 16th/17th C).

Perhaps this is why the Nahat ouds are preferred to represent 17th C Ottoman music today?

A quick analysis of the geometry of a 1905 Manol (based on a downloaded image) suggests that Manol did indeed modify this 'classic' geometry and so it

differs somewhat from the 'traditional' Turkish oud geometry.

More to follow on the Manol geometry for comparison.

|

|

|

Ararat66

Oud Junkie

Posts: 1025

Registered: 11-14-2005

Location: Portsmouth, UK

Member Is Offline

Mood: mellow yellow

|

|

Really interesting post, I'm watching quietly.

Thanks

Leon

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

In the absence (sadly) of an original Manol to work with, it will be necessary to 'make do' with the best image available in order to analyse the

design geometry used by this luthier. There are a few images of Manol ouds available on the internet but most are unsuitable for analysis as the

images are not taken at 'full face' view.

The best image so far available is one posted by Hank Levin on this forum some time ago of his 1905 Manol that is complete with its original sound

board. No dimensional information - string length etc - that might otherwise be useful is available.

A preliminary analysis of the profile of this oud indicates that it may be a modification of a more ancient geometry - perhaps in order to shorten the

relative string length?

Otherwise, the geometry does not match the 'traditional' (modern?) Turkish oud geometry previously posted but may be an intermediate design that might

eventually have led to this modern day concept.

More to follow!

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

For a more general up to date history of the Ottoman Empire, the publication "The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe" by Daniel Goffman, Cambridge

University Press 2004 is well researched and clearly presented. An interesting and informative read.

|

|

|

Jonathan

Oud Junkie

Posts: 1582

Registered: 7-27-2004

Location: Los Angeles

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

A very interesting thread, although when I first read the subject line, I assumed it referred to the scarcity of Turkish ouds that date from the era

following the creation of the modern Turkish state and, in particular, the 1930s.

I beliee that he scarcity of ouds from earlier centuries us due solely to the passage of time, and the fragile nature of ouds.

Manol's impact on the development of the modern Turkish oud cannot be overstated but, for what it's worth, I have an oud from Thesoloniki (I believe

that was a part of the Ottoman Empire at the time) from the 1890s that, for all intents and prposes, looks, sounds and feels like a Turkish oud.

I am priveleged to own the Manol posted above, and i will gladly forward information on its measurements-it will e a couple of weeks until I have

access to it again, though.

|

|

|

Ararat66

Oud Junkie

Posts: 1025

Registered: 11-14-2005

Location: Portsmouth, UK

Member Is Offline

Mood: mellow yellow

|

|

The Manol shape and proportion is truly a thing of beauty - my Tasos oud share much of this geometry - I'd love to try an original one day.

Leon

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Thank you Jonathan - that is good news.

As I am working with a relatively low resolution reduced scale image, that may have some degree of optical distortion, some percentage dimensional

error may be expected. Also there may be some degree of asymmetry in the oud profile. So I shall first post images of what I believe to be the

geometry of this example of a Manol oud independently of any dimensional information. Then the exact dimensions measured from the original instrument

will help to verify the precision (or otherwise) of the proposed geometry.

Note that the early oud and lute geometries seem to have been based upon relative proportions, belief in the significance of numbers as they relate to

material matter in the Universe (numerology) and the use of Euclidean geometry where all constructions (and proofs) are accomplished by using no more

than a straight edge and dividers (or compasses).

As the lute is supposed to be directly related historically to the oud (rather than being a completely independent development) one might expect to

find key geometrical components in comparing lutes and ouds of different historical periods as well in the comparison of oud development over time.

One problem is the lack of original surviving artifacts. There are no ouds of any type surviving prior to the late 18th C or early 19th C. The reason

for this may be not only the fragility of the instrument but the fact that the oud - unlike the lute - has enjoyed an unbroken tradition so

replacement instruments have always been readily available. So although the oud fell out of favour in the Ottoman court music of the 17th and 18th C

it continued to flourish elsewhere within the Ottoman Empire.

As far as the lute is concerned interest in that instrument died completely by the mid 18th C. Interestingly, although the lute is also a fragile

instrument, many original lutes still survive from the period dating from the early 16th C to early 18th C - probably because most are works of art in

themselves and so were preserved - admired, in their silence, as decorative artifacts.

If the oud and lute are directly geometrically then a study of the surviving lutes might go some way to providing or confirming some information

about the likely form of some ouds dating prior to the 19th C.

Next to get to work with dividers and straight edge!

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

For more details on the general principles employed in the proposed geometrical constructions go to the topic "Old Oud compared to Old Lute Geometry"

on this forum.

Starting with an oud profile based upon a Pythagorean 3:4:5 right triangle with neck length equal to the distance from neck joint to centre of rosette

and from centre of rosette to bridge and with the bridge 3 'finger' units from the X axis (widest point of sound board). This represents the geometry

of the Nahat style of oud which in turn seems to have been developed from the 9th C 'Ikhwan al-Safa' oud profile.

The objective of Manol seems to have been to reduce the string length of the oud while preserving all of the relative proportions of the other

components such as rosette position, bridge position, bowl width etc of the original traditional profile. This is achieved by moving the neck joint

location towards the bridge by a distance of 1 'finger' unit and making the neck length and distance from neck joint to centre of rosette equal. The

upper sound board profile is then described by the radius R-Manol shown on the attached diagram. Although this layout appears to match the profile of

the 1905 Manol oud image very closely the 'traditional' proportions based upon a 3:4:5 triangle with neck length being 1/3 string length no longer

applies.

The rosette arrangement is shown in the attached image.

Going one step further if the widest point of the sound board is then lowered towards the bridge by 1 finger unit to a new Y axis then the

'traditional' proportions of neck length to string length are maintained as is the 3:4:5 triangle construction (now located on the new Y axis).

This construction is almost identical to that of the geometry of a Turkish style oud described by Eren Özek in an article published in 'Müzik ve

Bilim', March 2005.

The only problem is that the new upper sound board profile generated by radius RY does not quite match the upper sound board profile of the 1905

Manol. So is this discrepancy due to optical distortions in the image and scaling error or did Manol - for this instrument decide to modify the upper

sound board profile. Or did the oud as constructed not quite match the designed profile?

Of course no positive conclusions may be drawn from the analysis of only one instrument by Manol and is is likely that he may have built ouds to a

number of slightly different geometrical constructions. This analysis does tend to confirm, however, that this may have been the construction used by

Manol for his Turkish style ouds.

The string length for a full size (man size) Turkish oud today is 58.5 cm. Why?

Is this the string length of the 1905 Manol oud?

Only questions at this point in time.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

If it is true that the oud, as a high art instrument, went out of fashion by the 17th C in the Ottoman court (based in Istanbul - formerly

Constantinople) only to be 'reinvented' in the late 19th C (as what is now known as the Turkish oud) - how could this have happened?

The 17th C German scholar, musician and composer Michael Praetorius provides a somewhat biased perspective in his monumental and important work on

musical instruments - Syntagma musicum (music encyclopedia). The Volume I of this work was written in Latin - Latin and Greek then being the language

of the European scholarly elite. Volume III dealing with musical form and theory and Volume II (De Organographia) providing descriptions and scaled

drawings of musical instruments known to him, on the other hand, were written in German, the common language. Praetorius did so because he considered

that most musicians and artisans had no facility in Latin or Greek.

The publication of Volume II in 1619 begins with a dedication to his sponsors and patrons of the Leipzig town council giving a brief history of the

ancient instruments of Israel. He then launches into a brief diatribe against Islam and the 'barbaric' music of the Ottoman Turks. No doubt his

objective was to tell his readership what it wanted to hear - the Ottoman armies having invaded as far North as Vienna before being repelled and so

were still considered to be a very real threat to the German states.

Praetorius refers to the longest reigning Sultan of the Empire (1494 - 1566) - known in the West, for good reason, as 'Suleiman the Magnificent' - as

that 'Turkish butcher'. Regardless of the horrors and brutalities of war of any army - European or Ottoman - Suleiman I was, by all accounts a highly

educated man, a competent leader and social and administrative reform innovator. Under his patronage culture and art prospered. He himself was an

artisan (goldsmith), a poet proficient in many languages including Turkish, Arabic and Persian (the languages of the court and government).

More to follow.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Praetorius (latinised version of Schultze, his family name) was the son of a Lutheran pastor. Born in 1571 his comments about Suleiman I were,

therefore, popular hearsay as - perhaps - were his remarks about Ottoman Turkish music.

He tells us that the religion of Islam forbade not only the liberal arts but anything that could make people happy including the music of strings.

This music was replaced by the bell, drum and shawm (a loud type of double reed pipe), 'wretched' music that was highly esteemed among the Muslims for

merry making, celebrations and in war. (Praetorius was here, presumably, referring to the Janissary military band).

He goes on to give an historical example of a gift of a large musical instrument (a pipe organ) given to Suleiman by king Francis I of France (France

and the Ottoman Turks were allies at the time). The gift together with the accompanying French musicians were so well received according to Praetorius

that people flocked to hear the delightful music - so that Suleiman - fearful that his people would become 'civilized' had the instrument destroyed

and the musicians sent back to France!

Praetorius goes on further to say that he includes illustrations of the 'barbaric' instruments used in Muscovy, Turkey, Arabia, India and America "so

that we Germans may become acquainted with them as well; not, of course, in the sense of using them ourselves - but simply to know what they looked

like!"

He provides three pages in Volume II of his book illustrating 'barbaric' folk instruments including one showing Turkish drums but no other Turkish

instruments - not a stringed instrument in sight.

By way of contrast he provides many illustrations of the full range of European instruments including a page showing various lutes and other plucked

instruments.

Clearly Praetorius was exaggerating the situation as far as music of the Ottoman Turks was concerned - perhaps for political reasons or just out of

ignorance. Nevertheless was there a grain of truth in his opinions? Could it be that Suleiman had no great interest in music as an art form

particularly given that the overriding law of the empire was the Shari'ah law where the oud itself may have been banned and therefore excluded from

the Ottoman court as well as in the Muslim society? If so did the oud only survive for the next two centuries among the non - Muslim societies that

were tolerated and protected within the Ottoman empire as "people of the book"?

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

It is said that one of the great strengths of the Ottoman empire at its peak of power in the 16th C, like other Islamic societies, was its tolerance

of other religious groups who followed the sacred writings of Judaism and Christianity. These groups "People of the Book" - for the cost of a 'head'

tax - were protected and allowed to practice their religion under their own laws and jurisdiction. The empire thus became a safe haven for persecuted

Christian groups who were able to escape from the European Catholic versus Protestant conflicts of the 16th C and later.

The Ottoman empire, at its peak, controlled trade routes to the East and access to the silks and spices in demand in Europe. The merchant 'middlemen'

who moved freely between both Europe and provinces of the Ottoman empire to conduct trade were rarely Muslim but more often Jews or Armenian and Greek

Orthodox Christians and later the Levantines.

The ongoing Christian religious conflicts in Europe also resulted in political and economic alliances with the Ottoman Turks.

The earliest of these was with France in the 16th C - an alliance that was to endure for 250 years until Napoleon invaded Egypt in the late 18th C.

France benefited from this alliance not only in having a trading monopoly in the Mediterranean but the Catholic French King Francis 1 was able to

successfully attack his arch enemy the Habsburg Emperor Charles V with the support of the formidable Ottoman armies. Francis 1 had ambitions to become

the Holy Roman Emperor in place of Charles V but eventually without success.

A later alliance with the Ottoman Turks was with Elizabeth 1, Queen of England, who supplied arms and raw material such as lead and tin to Morocco -

much to the dismay of Catholic Spain.

Another interesting historical 'twist' in the relationship with Europe and the Ottoman empire occurs as a result of the religious reform in the early

16th C against Roman Catholics and the Pope - a movement led by Martin Luther. With the impending attack on Vienna by Ottoman forces, Luther did not

support the Turkish endeavours (although some of his fellow countrymen did) but was ambivalent seeming to prefer the 'Turks' above the Pope and

Jews.

The Ottomans felt closer to the Protestants than to the Catholics. Suleiman I, at one point, sent a letter of support to the "Lutherans" in Flanders

"since they did not worship idols, believed in one God and fought against Pope and Emperor".

Later Sultan Murad III sent a letter to the Lutheran sect in Flanders and Spain highlighting the similarities between Islamic and Protestant

principles.

So, with an apparent symbiosis (albeit politically inspired) between the Ottoman Turks and European Lutherans in what direction might this take us

concerning the oud in Istanbul of the 16th C and lute in 16th C Europe?

More to follow

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

The famous enigmatic painting "The Ambassadors" was painted in 1533 by Hans Holbein. It depicts Jean de Dinteville French Ambassador to the English

court of Henry VIII in London and his friend and Catholic cleric Georges de Selve Bishop of Lavaur and one time Ambassador to The Emperor, the

Venetian Republic and the Holy See.

The figures and articles in the painting appear to be rendered with photographic accuracy and in precise perspective view and include many items from

the Near East such as a Turkish rug and navigational or surveying instruments of Arabic or Persian origin. In the forefront of the painting is a

representation of a skull - no doubt a reminder of inevitable death (Memento Mori) - that must be viewed at the correct angle to be observed in its

correct proportions.

The painting, probably a gift from the unknown person that commissioned the work - was once displayed in the Palace of Jean de Dinteville in France -

no doubt a popular conversation piece among family members and friends.

Much effort has been spent by scholars in analysing the painting in detail and attempting to explain the apparent riddles and symbolism inherent in

the work.

The scientific instruments - sundials, quadrants, celestial globe etc are all set to the date 1533, the year that Henry VIII divorced Catholic

Catharine of Aragon, married Ann Boleyn and declared himself head of the Church in England - all in defiance of Papal authority - actions that

resulted in his excommunication.

The Polydedrial Sundial (on the top shelf, next to the elbow of Georges de Selve) is set to a Latitude that is not that of London but North Africa

(Barbary Coast?)

In the centre of the picture, on the lower shelf, is a representation of a lute and a case of flutes with an open Lutheran Hymnal alongside containing

compositions of Martin Luther himself. There is also a book of Arithmetic, a folding square and pair of dividers on the same shelf.

This poses one of the, as yet, unsolved mysteries of the painting. Why would a book of hymns by the then 'notorious' Protestant Reformer, Martin

Luther (from the Catholic Christian perspective) appear so prominently in a painting depicting two men of opposing Christian doctrines?

The answer may lie in the Franco-Ottoman alliance two years later - which was declared an "unholy alliance" - but served to curtail the ambitions of

Habsburg Emperor Charles V in Europe and is thought to have been the reason that Lutheranism survived and developed in Germany by the second half of

the 16th C. The primary factor contributing to this political and religious development was Ottoman imperialism.

It is not known who commissioned the "Ambassadors" painting or why. One suggestion is that it may have been Anne Boleyn who was a Reformist

sympathiser and a patron of Hans Holbein the artist.

Now to focus on the lute represented in the painting. Can this tell us anything about the form of the oud as it may have been in 16th C Istanbul?

High resolution images of the painting can be viewed on the National Gallery, London website.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Martin Luther had a formal musical education at the University of Erfurt where he learned lute and flute. He was a capable lutenist and always carried

his lute on his travels.

So - in addition to the Lutheran Hymnal in the "Ambassadors" painting it is likely that the lute and case of flutes also alludes to Luther.

The lute represented by Holbein appears to be typical for the time with six courses and eight frets on the neck - except for the rose that does not

appear to be 'cut in' to the sound board but is separate and glued under the sound hole like an oud of today.

Forum member ALAMI - using computer graphics software - recently rendered the image of Holbein's lute from perspective view to orthogonal projection

(full front and side view) as shown in the attached images. He found that the profile of the lute was a close match to the lute geometry given by

Henri Arnault de Zwolle in the mid 15th C. Surprisingly, however, the neck is quite short, only long enough to carry six frets - good for an oud but

not a lute of the time. So is this another riddle woven into the painting by Holbein? Did he use an oud for his model - in keeping with the other

artifacts of Near Eastern origin (i.e. the Ottoman Empire) as represented in the painting but chose to paint it to represent a lute (easily done by a

painter)? Was he intending to allude to the origins of the European lute perhaps?

Holbein is often said to have been a master of precise perspective representation. However, close scrutiny of the image of the lute shows that the

perspective is imperfect - giving the lute a slightly twisted appearance. Another example of inaccurate perspective rendering can be seen in the

handle of the terrestrial globe. So Holbein's perspective views of some of the objects in this painting would seem to be more intuitive than accurate

- cleverly fooling the eye of a casual observer - a 'trompe l'oeil' - the stuff of artists!

Further evidence that Holbein may not have rendered the perspective of the lute correctly can be seen in the lute case almost hidden under the

shelving. Assuming the lute case is meant to be for the lute in question, it is evident that the case is designed to hold a lute with a more correctly

proportioned, longer neck.

Is this the oud design that was being made by luthiers of the Ottoman Empire perhaps introduced to luthiers of the German states by 'middlemen'

traders such as the Armenians. Hard to say from this 'evidence'.

Curiously, there would appear to be another historical connection with early oud design, lute design and the Lutheran church.

More to follow.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

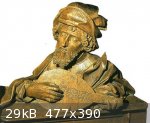

The familiar carving of 'Pythagoras with Lute' by Jorg Syrlin the Elder is in the Lutheran Church in Ulm, Germany. The large church or minster is

sometimes referred to as a 'cathedral' because of its size although it never was the seat of a Bishop.

So, is this representation of a lute another link with Luther's Protestant Reformation? Apparently not to judge from the history of events.

The foundation stone of the church was laid in 1377 when Constantinople was part of the Holy Roman Empire.

The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman armies was in 1453.

The carvings in the church were created by Syrlin between 1469 and 1474.

Martin Luther was born in 1483

The citizens of Ulm by a referendum converted to Protestantism in 1530.

Nevertheless the lute represented by Syrlin may well have been derived from an oud design being made by luthiers in Constantinople and neighbouring

states in the region prior to as well as following the capture of the city by the Ottoman Turks - possibly luthiers of Christian faith? Could this be

the style of oud that was still being made in the region during the 16th and 17th C hiatus of the instrument in Ottoman court music? Did some of these

luthiers as a consequence find it economically beneficial to move to other regions of the Ottoman Empire (such as the Levant, Syria, Egypt or the

North African 'Barbary coast' in order to practice their craft?

One late 19th C lute made by the (Christian) Al-Arja Brothers seems to closely match the Ulm lute geometry and so may have been made to an earlier

luthier tradition handed down through the centuries?

A full discussion of the comparisons between the Al-Arja oud and the Ulm lute can be found on page 2 of "Old Oud compared to Old Lute Geometry" on

this forum.

It would be interesting to analyse the geometries of surviving old ouds made by luthiers originally from Armenia and Greece to try to find out if

there might be other examples conforming to the Ulm/Al-Arja design - at least as far as the upper sound board profile is concerned.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

The exclusion of the oud in the Ottoman court may have been initiated by Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent who, in strict accordance with Muslim law,

banned wine drinking and dismissed the palace dancers and musicians, replaced silver plates with earthenware and ordered musical instruments set with

gold and precious stones to be burned. Wine drinkers were discouraged from enjoying their habit by having molten lead poured down their throats! So

Praetorius may have been more or less correct in his observations about the Ottoman court in Suleyman's reign. The fate of practicing musicians at

this time is not known. Hopefully king Francis I musicians, on loan, were returned to France in one piece!

However, Sultan Selim II (1566 - 1574) on succeeding his father, repealed the alcohol drinking ban - draining his glass of wine he is said to have

remarked that "I live for today, and think not of tomorrow".

It is not known at present if Selim II or his successors (who were also wine drinkers) had particular interests in music or, more specifically, the

oud.

|

|

|

Danielo

Oud Junkie

Posts: 365

Registered: 7-17-2008

Location: Paris

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Selim III (1761 – 1808 ) certainly had - some of his compositions are still played today. He played the tanbur and the ney. About the oud, no

idea.

Dan

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Thanks Dan.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

I am still trying to get a better understanding of why - apparently - some musical instruments had their place in the 16th and

17th C Ottoman court when others did not. Some historians say that the traditional instruments of the court were the Tanbur (long necked fretted

lute), the Ney (end blown flute), the Kanun (zither), Kudüm (drum), Tef (tambourine) and Zil (cymbals). So there would have been a strong percussive

element to the music of that time. There is mention of the oud (as well as bowed instruments) being incorporated into the high art music at a later

period yet the oud must certainly have existed in the regions surrounding Istanbul as well as in the city itself in the 16th C and later.

Was it a matter of religious versus secular preference (or dogma)? Was the oud, for some reason, outlawed in the strict Muslim society of the Ottoman

court of that time yet the Tanbur was not. If so, why? Did the oud have too strong a secular association?

Only questions at this point!

|

|

|

ALAMI

Oud Junkie

Posts: 643

Registered: 12-14-2006

Location: Beirut

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

I don't think it is religious versus secular, in traditional Islam only percussion instruments are allowed, so I don't see any reason that would allow

tanbur or ney and ban oud. A nationalistic reason would be more logical, the oud being " less Turkish" and was widely used in Arab courts and probably

Safavid court also. But the Kanun is also not exclusively Turkish.

May the absence of the oud from court ensembles was due to a practical reason: volume and loudness. Tanbur,yayli tanbur, ney and kanun are way

louder than oud.

When I think of those huge rooms in Topkapi, filled with people, you need some volume.

I don't know, just a thought.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Thanks ALAMI

I understand that both the Ney and Tanbur did have sacred significance among some religious sects (extending to the20th C) but perhaps not in the

Ottoman court at least until after Suleiman1 where strict application of Muslim doctrine seems to have given way to a more 'relaxed' interpretation of

the religious law?

A large palace room filled with people would certainly demand a high volume output from a musical event that no doubt is the reason why orchestral

music took preference in the 17th C. I am not sure, however, if any of the non percussive instruments (ie the Ney and Tanbur) were then particularly

loud instruments bearing in mind that the Tanbur was strung with silk (or gut) strings like the oud whereas today metal strings seem to be the norm

with, presumably, a louder sound (very modern!). I am not sure about the Kanun (Dulcimer) which might have been either a percussive instrument (using

'hammers' to strike the strings - louder) or plucked (less loud)? Of course, increasing the number of instruments of each type would result in

increased volume overall.

As vocal music was part of the traditional repertoire at least some of these instruments would have been used to accompany the singers and so (unless

the singers were practicing an early 'Bel Canto' technique) would have to be sufficiently low in volume to give precedence to the human voice probably

in a more intimate setting than a large palace hall?

Again no answers only questions.

I am still puzzled as to why when the oud was re-introduced to Turkey in the late 19th/early 20th C that the traditional design (apparently?) was

modified (if it ever was - by Manol?) rather than adopted, unaltered, from established traditional designs.

Perhaps a detailed examination of the geometry of surviving ouds from Turkey and neighbouring regions might provide some answers?

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2

3 |