| Pages:

1

2

3 |

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Wood Fit for a King? - an investigation

In chapter 6 of "Structure of the Arabian and Persian Lute",

Dr H. G. Farmer translates part of the 15th C. Kitab kashf al-humum (preserved in the Top Qapu Saray Library at Stamboul) including comments about the

best woods from which to make an oud.

According to Salih ibn 'Abdallah ibn Karim al-Nisaburi, the ancients used four kinds of wood (for the bowl?) these being Beech (zan), Elm (dardar),

Walnut (saz = shiz= sasam) and Vine (mais) - which have qualities not found in other woods. He goes on to give some of these qualities. Beech gives a

ringing tone; elm gives a fineness (of tone?); walnut lasts forever and resists insect attack. For Vine he makes the mysterious comment that it has a

quality 'only to be found in the treasury of kings'.

I have never used Vine as a wood or know of it being used for instrument making in modern times. If the Vine referred to is Grape Vine (or a species

of Grape Vine), it is a wood that is common to this part of the world. Indeed, as a woodlot owner (a tree farmer - of sorts), I regard the wild vine

as a pest plant in that it grows quickly and can eventually overcome and kill any tree that it climbs. For this reason part of maintaining the wood

lot is to cut any vine found climbing a healthy tree - a never ending task. The tree farm was planted about 25 years ago on redundant farm land but

there are also many trees of venerable age growing in the original field fence-lines of the farm - including some large, well developed vines. Rather

than clear out and waste these old vines, I thought that it might be interesting to use them in an experimental investigation to determine if this

wood might be suitable for oud making.

I shall start with a vine patch that has stems over 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter. This vine plant appears to be dead so the wood may be partially

seasoned (if it is not rotted). There are also many vines of lesser size - cut in recent years and now dry - to experiment with.

Vine seems an unlikely wood to me but there is only one way to find out. "Nothing ventured, nothing gained".

This is not a good time of year to work in the woods due to the high humidity and proliferation of biting insects so will likely get into the project

later this year.

In the meantime, does any one know of Vine being used in modern times for oud bowl construction - or any kind of woodwork for that matter?

|

|

|

GeorgeK

Oud Addict

Posts: 46

Registered: 7-16-2008

Location: Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Very nice topic, I look forward to reading how this progresses.

I'm curious on how you plan on experimenting with the wood? Are

your interests from a structural point of view or are you planning

on doing some tone quality experiments? If its the latter then,

if you dont mind, can you post on how you plan to proceed, ie

experiment setup, how you plan on rating the quality of the tone, do you plan on comparing varoius species of wood, etc...

Again, a very nice topic and I look forward to your progress.

|

|

|

SamirCanada

Moderator

Posts: 3405

Registered: 6-4-2004

Member Is Offline

|

|

I thought Sesam refered to Indian Rosewood.

|

|

|

Marina

Oud Junkie

Posts: 615

Registered: 9-1-2005

Location: Bosnia

Member Is Offline

Mood: Enthusiastic

|

|

Samir, I also got the oud with Sesam bowl - newer know what does it mean.

Walnut or Indian RosewoodEnybody? It has reddish color.

|

|

|

paulO

Oud Junkie

Posts: 535

Registered: 9-8-2004

Location: California

Member Is Offline

Mood: Utz

|

|

Looks more like a type of rosewood to me. The walnut I've seen has less pronounced contrast in the grain and tends to be more of a uniform brown. This

is one beautiful oud, whether walnut or rosewood !

Regards,

Paul

|

|

|

DaveH

Oud Junkie

Posts: 526

Registered: 12-23-2005

Location: Birmingham, UK

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Interesting concept. I have this image in my head that vinewood would have a very low density and splits all over the place, but maybe that's because

of the way the bark looks and feels. I realise I've never actually seen the heartwood.

We are talking of the days of Omar Khayyam here, so I'm guessing if vinewood was used then it was from vineyards and was torn up because the vines

were past their best for fruiting. I'm wondering, if it was very old and had been constantly pruned, it might have ended up denser, harder and

gnarlier, a bit like olivewood or walnut. So, if this doesn't work out so well with wild vinewood, it doesn't necessarily discount your theory.

Another thing I was wondering along these lines - could this reference have been allegorical, or even a sly joke, referring to the fact that vine was

so highly prized by the secular authorities (but not really approved of by the religious ones). Maybe even something along the lines of music sounding

better when you're wasted  . Or perhaps the courtiers preferred to be inebriated

when their kings picked up the oud, what with them having so many other responsibilities and so little time to practice - I've been there. . Or perhaps the courtiers preferred to be inebriated

when their kings picked up the oud, what with them having so many other responsibilities and so little time to practice - I've been there.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Not sure about rosewood - I am just quoting Farmer who translates saz=shiz=sasam as walnut. Is 'sesam' the same as 'sasam'? B.t.w. Indian rosewood was

never used for European lutes as it was considered to be an inferior 'tonewood' - perhaps it was the same for early ouds? Indian rosewood has quite an

open grain whereas European walnut is close grained - more suitable for thin ribs I would say (American walnut, is a bit more open grained). Walnut

colour can range between brown and purple and can be very highly figured.

At this early stage, I am just researching available information so have yet to decide on what tests to carry out should the project seem viable. I

might very well end up making an oud with grape vine wood ribs to test my findings. Not sure about comparative 'tone quality' experiments though - too

subjective and life is too short!

Grapes were cultivated in early Arabic cultures to be used for distilling alcohol, not for consumption as a beverage, but for medicinal purposes - it

is said!

So far, I have found few literary references to (grape) vine wood as a woodworking material. These days it is often used for open fire cooking (BBQ)

as it is aromatic when burnt and provides a flavour to cooked meats.

One ancient reference to vine wood is in Ezekiel chapter 15 of the Old Testament of the Holy Bible. I am not qualified to interpret this parable but a

literal summary is that wild vine wood is no good as a woodworking material. It is only good for burning! So, perhaps I am 'barking up the wrong tree'

here and should not waste any more time on this project?

A more recent reference to vine wood is found in the mid

19th C publication "Turning and Mechanical Manipulation, Volume 1" by Charles Holzapffel. The first part of the book deals with materials for turning.

Under 'Apricot - Tree', the author refers to the 18th C French turner, Bergeron, who comments that often those woods that bear agreeable fruits are

not handsome in appearance or agreeable in scent as might be expected. In this category, in addition to Apricot wood, he lists Orange, Lemon, Quince,

Pomegranate, Coffee and Vine "and many others occasionally met with, rather as objects of curiosity, than as materials applicable to the arts"

Both sources indicate that vine was not considered to be a generally useful or commercially available woodworking material - for whatever reasons.

Nevertheless, could vine, in rare circumstances - carefully selected for a specific application - still be a perfectly viable material for making oud

bowls? Lets try and find out.

This afternoon I gathered two small samples of wild grape vine from my wood lot. These had been cut over a year ago so were relatively dry and

seasoned. The samples were each sliced in two on a band saw and the sawn surfaces planed smooth to reveal the grain. The large sample measures 50 mm

in diameter and the small sample 25 mm. No checking or splitting due to drying of the samples is evident. The heart wood is light brown with white sap

wood - medium open grain but less than American Walnut. Inspection of the end grain shows that it is a wood of 'ring-porous' classification - that is

it is a hardwood with relatively small (but visible under low magnification) pores in the early wood and very small (indistinguishable under low

magnification) pores in the late wood. (Other ring porous wood species include Elm, Oak, Ash, Hickory, Chestnut and many others).

Counting the rings in the large sample indicate its age to be about 25 years - so wild vine is not such a fast growing wood after all.

I would judge the density to be 'medium' or perhaps 'medium/heavy' - just guessing, around 0.5 to 0.6 Specific Gravity.

|

|

|

SamirCanada

Moderator

Posts: 3405

Registered: 6-4-2004

Member Is Offline

|

|

it would probably make for one light oud!

anyways would there be enough wood to make an oud with it??

could it be easily bent? I would think so.. Perhaps with less spring back?

also what part would be used the heatwood or sapwood?

thanks for this John.

its really interesting!!

as for sessam, the word is used now days to define indian rosewood by the oud makers of Iraq more particularly.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Thanks Samir.

Ouds of today would appear to be much more heavier built than early ouds - using denser hardwoods and thicker sections (and presumably much higher

string tensions and different tone colour) than would have been found in earlier times. Farmer in 'Structure of the Arabian and Persian Lute in the

Middle Ages' quotes from several early texts including:

"It is necessary that the wood of the bowl should be as thin as possible and of even thickness throughout ....". (9th C)

"The wood of the bowl should be thin and made from light wood.." (10th C)

"Seasoned Larch wood should be cut very thin for the soundboard. The bowl should be of thinner wood than the soundboard. The bowls of the best ouds

are made from 11 ribs but sometimes 13 are used" (14th C)

"The wise agree that wood of medium weight is required for an oud - the best wood being 'shah' from Darya-bar or sometimes from Sardia.." (14C)

"An essential to the oud is wood as thin as possible ...... It is agreed that the lighter the wood the better ..." (15C)

From this it would seem that an oud during this time period was constructed more like a European lute with rib thickness of the bowl less than the

thickness of the soundboard. (Rib thickness in surviving lutes can be around 1 mm to 1.5 mm thick).

Indian Rosewood has a specific gravity of around 0.76 compared to Black Walnut (0.55), Elm (0.5 to 0.66), American Beech (0.64), Hard Maple (0.46 to

0.63), Ash (0.56 to 0.61). For comparison Spruce has an s.g of 0.4, Larch 0.52 and Ebony 0.90. So, if my guess is correct and the Vine wood sample has

a specific gravity in the range 0.5 to 0.6 then this would not be out of place as a wood used in the construction of early ouds whereas Indian

Rosewood, Ebony and other dense tropical hardwoods would be considered too heavy.

The heartwood of the vine would be generally used - although the strong colour contrast between heartwood and sapwood might be a useful possibility

(like 'shaded' yew ribs in lutes). The sapwood of vine may not be very durable, however.

The question " would there be enough to make an oud with" is probably the most important consideration. I would not question that the early oud makers

knew what they were talking about when they list vine wood among the superior woods for oud making but obtaining sufficient vine wood, large enough in

diameter and straight in grain from which to make an oud could be a challenge. The biblical reference previously posted implies that it would be

difficult enough to find vine wood large enough to make pegs from let alone anything of larger size. This most likely means that an oud made from vine

wood would have been a rare instrument indeed - hence "only to be found in the treasury of kings".

The attached images illustrate the dilemma. The tangled, twisted mass of old vine stems (about 2 metres high) is the material that I am interested in

investigating. The large diameter stems buried in the middle of this tangle may be large enough and long enough to work with - but could also turn out

to be unsuitable. Not only do the stems curve but they also twist. Vines growing up living trees are generally straighter so may be a better choice -

if larger diameter stems can be found.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

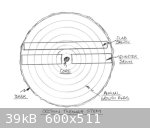

The rib blanks for an early oud with 11 ribs would have measured around 30 inches X 2 inches (760 mm X 50 mm). If the rib blanks were 'sawn on the

quarter', this would require a straight section of vine wood at least 4 inches (100 mm) in diameter. However, if the ribs were "slab sawn" a smaller

diameter vine wood stem could be used.

The attached sketch illustrates the difference between quarter and slab sawn sections for those unfamiliar with this terminology. Either way the core

or pith of the stem is never included. Quarter sawn is the most stable cut as the grain length is minimal and evenly distributed across the rib

section (wood shrinks most in the direction of the cross grain - the longer the grain length the greater the shrinkage). I am not sure if slab sawn

ribs were ever used on ouds (or lutes) but I do not see why not as long as the cuts are made close to the centre of the stem where the grain direction

is still partly on the quarter.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

The Specific Gravity of Vine wood.

This afternoon, the other half of the large sample of grapevine wood was cut to a uniform, squared section, about 5 inches (130 mm) long - on a

bandsaw. The sawn surfaces were then hand planed smooth.

The sample was measured dimensionally using dial calipers (resolution 0.001 inch) and the volume calculated to be 2.985 cubic inches or 48.92 c.c.

The sample was then weighed on a digital kitchen scale (resolution 1.0 grams). The measured weight was 31 grams.

The density of the sample, as measured, comes to

0.634 grams/cc. (I was brought up on the old grams/ centimetre/second and foot/pound/second standard systems - old habits die hard!).

Taking the density of water as 1 gm/cc this gives the specific gravity of the vine wood sample as 0.63. (Density is the weight of a unit volume of the

sample. Specific Gravity is the density of the sample compared to the density of water - a dimensionless number, useful for standardised comparisons

between various materials).

Note that the sample may not be completely 'dry' (moisture content of 8%) - so tests will be repeated on the sample to determine if there has been a

further reduction in specific gravity due to moisture loss. The test could be accelerated by drying the sample in an oven until an equilibrium point

is reached (determined by repeatedly weighing the sample) but, absolute accuracy in determining specific gravity is not critically important - it is

just useful for comparative purposes.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

A second sample of vine stem was cut from a different location in the woodlot yesterday. This sample is 'green' (full of sap), about 2 inches (50 mm)

in diameter and about 21 years old.

The specific gravity of a piece of the sample - prepared and measured the same way as for the first sample - was calculated, in this green state - to

be 0.75. This should reduce significantly as the sample dries out. This sample will also be used to observe how the wood responds to rapid air

drying.

Additionally, two sections were prepared - each cut through the core of the stem - in order to examine the sapwood/heartwood. The sapwood when freshly

cut was white but is turning to a pale brown colour after exposure to light for a few hours. It will be interesting to see if the entire sapwood areas

eventually turn to a uniform brown colouration to match the heartwood. The heartwood is medium brown in colour. In this sample there was evidence of

some localised 'heart rot'.

Both sections showed a pronounced 'ray fleck' or 'cross silk' figuring - particularly in the sapwood, as can be seen in the attached image.

According to one observer, grape vine wood is very brittle when dry. This will be another physical characteristic to verify as the wood may also

become harder and stronger and more resonant (as well as lighter in weight) when dry - which could be desirable for instrument making.

|

|

|

carpenter

Oud Junkie

Posts: 248

Registered: 8-30-2005

Location: Eugene OR

Member Is Offline

Mood: brimming with hope

|

|

It's probably not got anything to do with "real" vine wood, but there's something here in W Oregon called "vine maple." It looks a lot like other soft

maple to me when cut, but it grows in multiple stems vs a single trunk. I've seen it on signs on the firewood guys' pickups - "Vine, seasoned." It

could be that "vine" was some colloquial term at the time way back when, for some wood that grew in that vine-y way.

And when it comes to light wood for bowls, I made a bowl from alder, pretty soft for a hardwood, and darn lightweight. Sounded great. My opinion is

that people will trip over themselves to buy an instrument made from fancy, figured hardwoods, even when it's not necessarily in their best interests

to do so. Yet another opinion is that the bowl contains an air volume in a particular shape, and is generally acting as a reflector; it shouldn't make

all that much difference what it's made of, as the top is doing the real work. (If I'm horribly wrong here, and I could be, I figure I'll get

corrected - and soon.)

Meanwhile, I await results on the grapevine. Looks like an interesting experiment. The flecks are a nice feature ...

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Hard to say if the 'Vine' referred to in the early Arabic thesis is 'Grape Vine' - but the latter most likely is the vine species referred to as this

would have been most generally available in the Middle East - significant for its wine growing regions - during the 15th C and earlier?

Farmer translates 'mais' as 'vine' - does this mean 'grape vine' or some other species? I don't know.

The early oud makers were certain that the wood used for an oud bowl did make a difference - the best woods "having qualities which do not exist in

other woods". They do concede, however, that "if these woods (i.e. beech, elm, walnut and vine) are unobtainable, others may be used but they are not

so good".

Thin, lightweight construction referred to as important by the early oud makers dictates the use of woods that are up to the task structurally - i.e.

hard, medium density and close grained. 'Grape vine' - with a specific gravity of about 0.6 (yet to be confirmed) - is not a 'light weight' wood -

but is equivalent to beech, elm, and walnut in this respect.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Thomas Mace, writing about the lute in 1676 says

" there are very good lutes of several woods: Plum-tree, Yew, Rosemary-air (a maple variety?), Ash - Ebony, Ivory etc. The two last (though most

costly and taking (i.e. pleasing) to the common eye) are the worst". So Mace is confirming that the very dense - and exotic - materials, like Ebony

and Ivory - are not the best for making lute bowls.The same would seem to apply to early ouds?

Just for interest, I weighed two of my lutes, made many years ago - copies of 16th C. lutes. The first (late

16th C, seven courses) weighed in at about 1.6 pounds (0.72 Kg), fully strung and the second (a larger, early 16th C, six courses) weighing about 1.8

pounds (0.81 Kg). I cannot remember how thick I had made the sycamore ribs of the bowls of these instruments - most likely around 1/16 inch (1.5 mm)

but perhaps a little heavier. A target weight for a lute of this period, with thinner ribs,would be around 1.5 pounds (0.68 Kg) I would guess.

Thinness = lightness.

I recall a past quote - but am unable to validate the source from memory - that a good lute is so light in construction that it 'trembles' (i.e.

vibrates) in the hand at the mere sound of a human voice.

The first sample of wild grapevine wood seems to have now stabilised in weight, with some slight shrinkage in dimensions due to loss of moisture. This

sample is mostly heartwood and was quite dry to start with as there are no shrinkage cracks (checks) following the recent moisture loss and shrinkage.

Recalculating, the Specific Gravity is confirmed to be about 0.62. Ambient humidity levels have remained around 70%+ for some time now so there might

be further slight changes as humidity levels drop but not much.

The second sample - about 50% sapwood/50% heartwood and 'green' (live and full of sap) - is a different story. A lesson in how not to season wood!

More to come.

|

|

|

SamirCanada

Moderator

Posts: 3405

Registered: 6-4-2004

Member Is Offline

|

|

yes please more to come

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

........ sample 2 was cut on 02 August from a live section of vine growing up a tree. Sample 1 contained mostly heartwood (from a rootstock stem cut

at ground level) whereas sample 2 contained a significant proportion of sapwood. It may be that vine "suckers" (like sample 2) contain more

sapwood.

Sample 2 was prepared by planing all sides square (dimensions 1.185 X1.354 X5.022 inches) which weighed

99 grams. The sample was left to dry naturally - just to see what happened. Not surprisingly - after 6 days the weight reduced to 78 grams due to

moisture loss and the sample split or 'checked' badly as expected. This is a very severe test (even with sustained humidity levels of 70% +) as the

sample, being cut on all six sides, suffers very rapid moisture loss from the exposed surfaces. This is not the way to season freshly cut 'green' wood

- especially wood with a high sap content like vine!

Another section of the vine was cut through the centre and left to dry over the same period. This section suffered circumferential distortion due to

shrinkage along the growth rings but without any radial shrinkage cracks (as seen in the section alongside in the attached image).

This test confirms that the best approach to preparing vine wood will be to cut the vine in Winter - when the sap content is at a minimum level - then

to coat the exposed ends of the vine with latex paint or wax (to seal the wood pores and limit moisture loss). To accelerate the 'seasoning' (drying)

process without causing cracking - the sections may then be cut through the centre and, temporarily, tied together until seasoning is completed

(determined by weighing each section until the weight is stabilised).

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

For information - R. Bruce Hoadley in his excellent and informative book "Identifying Woods" (The Taunton Press), briefly mentions grape vine in a

chapter on 'A-typical Wood' including a nice micro photograph of a Grape vine wood section with its relatively large, ring porous, early wood and

closely spaced, very small, latewood. (compare with image previously posted on this thread).

Hoadley mentions that 'Wisteria' vine (sample dimension about 3 inches in diameter) has a similar ring porous structure to grape vine.

|

|

|

GeorgeK

Oud Addict

Posts: 46

Registered: 7-16-2008

Location: Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Excellent Post and very thorough!! Thanks for sharing.

Those are some pretty big vines. I dont think I've ever

seen any grow that big in my part of Canada (Ottawa).

I look forward to more of your posts!!

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

I am located just East of Ottawa so it is almost certain that wild grape does grow in the rural areas around the city. As far as I can determine wild

grape (several varieties) is native to most parts of the U.S. and Canada. The largest vines would most likely be found in old farm fence lines and

woodlots where they have been allowed to grow undisturbed for decades.

Another source of grape vine might be in the wine growing regions of the continent. Cultivated vines on original root stock can be productive for over

100 years so vines of this age would be quite large in diameter. Vines from grafted rootstock last only 40 years or so by comparison although it is

likely that most commercial vineyards nowadays will be working with grafted vines to avoid the danger of losses due to viral infection and disease.

For comparison, the attached image shows sample 1 after air drying. It is mostly heartwood and the vine had been severed some time ago so this sample

was fairly dry to start with.

The half section of the stem - like sample 2 (but less severe) - shows some convex distortion of the cut surface after drying or seasoning. Annular

growth rings are a series of moisture containing cells arranged side by side in circles of increasing diameter for each year of growth. When wood is

dried, moisture is lost from the cells which then shrink in size - the more cells in a growth ring the greater the amount of shrinkage of the ring. So

the outer growth rings shrink more than the inner growth rings which results in the concave distortion of the cut surface after seasoning.

Half sectioning is a technique that may be used in the seasoning of small diameter logs as it minimises the risk of radial cracking due to built up

stresses caused by too rapid drying.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

For information and to further illustrate the distortion that occurs due to shrinkage along the grain of the growth rings, the attached image shows

another section of sample 2 that was slab cut when 'green' and allowed to air dry. Note the relatively little distortion in the central slice (quarter

sawn, short, equal length grain) compared to the outer slices (slab sawn, longer, unequal length grain).

The upper surface of the half section alongside was originally sawn flat when 'green'. Shrinkage is greater along the outer rings than along the

shorter, inner rings - hence the curved upper surface after air drying.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Quote <grape vine wood is very brittle when dry>

Now that I have some well dried samples to hand it is time to check this out.

A strip measuring 20mm wide by 140mm long and 2mm thick was prepared from the heartwood of Vinewood sample 1.

It was possible to easily 'cold' bend this strip into almost a circle without the wood fibres fracturing. Far from being brittle the wood is very

pliable (but not surprising perhaps, given the sinuous nature of the vine plant). This would make Vinewood a good material for basket making, no

doubt, but will it be suitable for making an oud bowl? Much too flexible perhaps?

The next test was to hot bend the strip - with the bending iron at a temperature hot enough to scorch the strip. The strip was easily bent at this

temperature to a bow shaped curve of 30mm radius. On cooling, the strip was found to be much harder and stiffer and held its 'set' well without

'spring back'.

For comparison, test strips were prepared from Ash, Yew, Beech, Elm, Maple and Walnut - all woods mentioned as best for either oud or lute bowl making

in early texts.

To check the relative pliability of these samples, a strip was held (at each end) between the thumb and forefinger of each hand and forced into a bow

shape until it was judged that the strip was about to break. The deflection at the centre of each piece was then measured. Measured deflections were

as follows : Ash 38mm; Yew 32mm; Beech 32mm; Elm 29mm; Maple 26mm; Walnut 19mm. Each sample was then hot bent into a bow shape - at scorching

temperature - to a radius of 30mm. After cooling, the samples were tested for relative 'stiffness' by pressing each end together and comparing the

force required (by 'feel'). The hot bent Vinewood sample was judged to be fairly close in stiffness to the Ash, Yew, Beech and Elm samples. Both Maple

and Walnut were harder to hot bend and a lot stiffer after bending.

It is concluded - from these rather rough, subjective trials - that Vinewood, although it is much more pliable than the other wood species under test

(when 'cold bent'), became significantly hardened with heat to a degree that would make it viable as a material for oud bowl ribs or staves.

Now to make an oud bowl from the stuff! Next year perhaps - after collecting and seasoning sufficient Vinewood.

|

|

|

patheslip

Oud Junkie

Posts: 160

Registered: 5-24-2008

Location: Welsh Marches

Member Is Offline

Mood: smooth

|

|

jdowning

Congratulations on a well thought out research programme. I admire your persistence immensely.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Thanks for your interest and kind words patheslip.

Yesterday's trials raised a few more questions that need to be addressed.

The hot bent sample of vinewood was tested to destruction by squeezing the open ends of the sample together. It failed by sudden, brittle fracture

well before the ends met - so the hot bent sample was a lot harder/stiffer than when it was just air dried and subject to cold bending.

Question 1 - how 'dry' was the vinewood sample under test?

Question 2 - did the scorching of the hot bent vinewood samples result in a hardening of the samples?

To investigate further, the original sample 1 (mainly heartwood) and sample 2 (about half heartwood/ half sapwood) were oven dried to remove any

residual moisture after a few weeks of air drying. At the same time a second strip of heartwood (from sample 1) was prepared for testing - to be oven

dried together with the test samples #1 and#2.

Oven drying of the samples (and the second test strip) was undertaken in a microwave oven (when my wife was absent!). Set at 60% power for 1 minute

periods, drying was repeated until the measured weight of each sample became stable and uniform - at which point each sample was assumed to be 'bone

dry' or devoid of moisture.

When freshly cut, the initial measured moisture content of sample 1 was about 29% and about 55% for the 'green' sample 2. After 20 days air drying,

with relative humidity levels fairly constant at around 70% +, the moisture content of sample 1 had dropped to around 12% which was the moisture

content yesterday of the first test strip prior to hot bending.

The 'bone dry' second test strip was found to be just as pliable as the partially air dried vinewood strip in yesterday's trial - from which it may be

concluded that complete moisture removal alone does not result in vinewood becoming less pliable or hardened. It was the scorching heat applied during

the hot bending process that 'tempered' or hardened the vinewood.

Flame hardening of wood is a technology used by "primitive" early civilizations to harden sharpened wooden arrow and spear heads (a method still

recommended in USA army survival manuals).

The attached image shows the brittle fracture failure of the hot bent vinewood sample of yesterday and the pliability of the 'bone dry' oven dried

second test strip of today - for comparison.

The oven dried samples now provide data from which to

re- calculate the specific gravity of vine wood - to follow next.

|

|

|

jdowning

Oud Junkie

Posts: 3485

Registered: 8-2-2006

Location: Ontario, Canada

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

The previous posting has been edited, primarily to correct errors in the measured/calculated moisture content of the samples under test and to make a

few changes to the text for clarity.

To summarise, the main observation, according to these most recent tests, is that vinewood retains its pliability even after oven drying to remove any

free moisture. However, after hot bending at temperatures sufficient to scorch the surface of the wood the wood loses its extreme pliability and

becomes hardened and stiffer. So it might be assumed that the high temperatures experienced in hot bending the sample alters the chemical/physical

structure of the cells of the vinewood in some way - sufficient also perhaps to drive out any residual moisture locked within the cells that might be

responsible for the pliability of the wood.

It should be noted that these tests involved accelerated drying methods in order to obtain quick results. It is possible that similar

chemical/structural changes in the cell structure might be achieved naturally by simply seasoning the vinewood for a year or two in the traditional

manner? Time will tell!

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2

3 |